Earlier this morning Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft was sat atop an Atlas V and ready to launch. Unfortunately, with around 4 minutes left in the count, the vehicle went into an automatic hold that eventually scrubbed the flight. This was the second attempt with the last one being scrubbed early last month on the 6th.

So far, we’ve received reports that the scrub had to do with a ground computer initially halting the countdown related to issues with it not loading in the correct operational configuration. While that was the reason for the scrub, there were a few other issues leading up to that point as well. Here I will go more in-depth into what happened, the next launch attempt, final mission prep, and more.

What Went Wrong?

With less than two hours left in the count, both astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams were strapped into the spacecraft. Soon after a few issues began to arise. Initially, two valves associated with propellant loading ground support systems were experiencing an apparent communications issue with launch control. These values are responsible for topping off propellant in the liquid oxygen and hydrogen tanks in the Atlas Centaur second stage. Specifically, this issue had to do with the Atlas V but was fixed soon after as engineers determined the issue was the primary telemetry stream, not the actual valves. They ended up switching the valve data stream to a redundant system and the clock continued.

With around 30 minutes left till launch, crews began leaving the launch pad after closing Starliner’s hatch and moving its crew access arm. The weather forecast at the time was also a promising 90% go for launch. With around 20 minutes left ULA flight controllers reported an errant temperature sensor reading in a sensor that they highlighted was not necessary for launch given the count. With that in mind, they decided to deactivate it a bit earlier than planned. There was also a small problem related to the astronaut’s space suits. With around 10 minutes left before the expected launch, the CFT commander Butch Wilmore reported a suit fan warning light. A few minutes later they were working again.

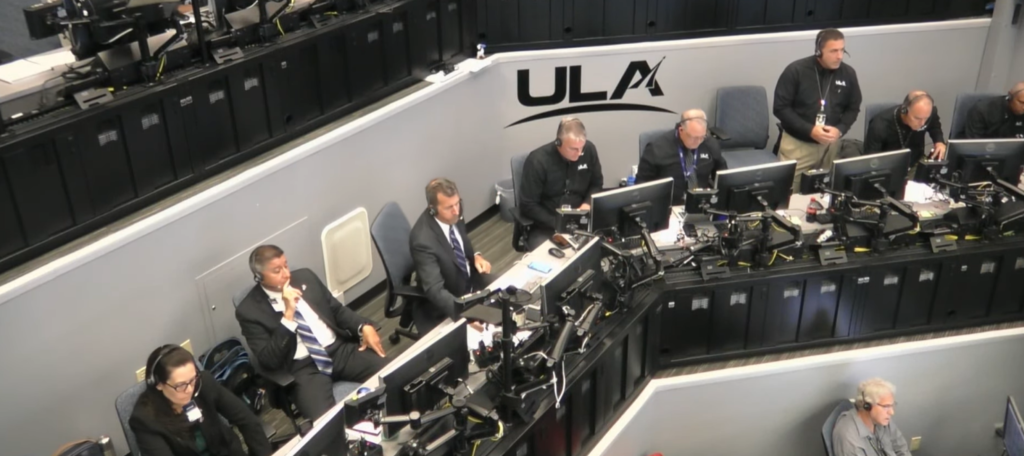

Despite all these different little complications, the flight was still a go and had just minutes left on the clock. That was until T-3:50 seconds when the flight controller called a hold. In this case, there’s a computer that launches the rocket when the vehicle goes into terminal count, also called the GLS or Ground Launch Sequencer. Something with the GLS caused it to throw an automatic hold out at T-3:50. In a NASA statement they clarified by saying that the “computer ground launch sequencer was not loading the correct operational configuration after proceeding into terminal count.” NASA held a press conference a few hours after the attempt and here, ULA CEO Tory Bruno clarified that they have three computers that create redundancy for certain final launch operations. One of these operations include the pyros for releasing the bolts that hold the rocket to the pad. For that system they require all three systems to be running. He was quoted saying, “each of those racks do a health check, and they monitor to see that those cards came up when they were commanded to come up and begin doing their job. Two came up normally, the third one came up but it was slow to come up and that tripped a red line that created an automated hold” he said. This issue was enough to scrub today’s attempt due to the planned timeline. The launch window for Starliner this morning was instantaneous meaning there were no plans for backup opportunities that same day. In other words, once the hold was triggered in the count, the launch was basically immediately scrubbed for the day no matter its severity. Thankfully for Boeing and NASA, the issue doesn’t seem to be too significant.

Already they have expressed an interest in attempting the launch again tomorrow morning on the 2nd. They first have to get access to that computer and determine why the issue occurred. They should be able to do this late this afternoon. By then they will know if the issue is a quick fix for a launch tomorrow or if it will take a few days. As far as the leak that was found after the last launch attempt in May, it didn’t create any issues with this morning’s attempt. Controllers reported that the leak rate was acceptable and had even decreased from past numbers. In the press conference held earlier today Steve Stich commented that it had about halved in leak rate. For context, a small helium leak was found related to the spacecraft’s RCS thrusters however Boeing and NASA determined that it was acceptable and could be left as is for the launch.

Future Opportunities

Besides June 2nd, there are a few other opportunities within the coming days. The three backup dates include June 2, June 5, and June 6. This means if they arent able to get the rocket and spacecraft ready by tomorrow morning, they will have a few days to fix any remaining issues and get the vehicles back on the pad early this month. That being said, it puts a lot of extra pressure to ensure this launch happens by June 6th at the latest. With this being the last backup opportunity a delay past this date could create some significant schedule issues. Something Boeing and the Starliner spacecraft need to avoid considering their history.

Yesterday Steve Stich, the NASA commercial crew program manager mentioned that ULA would need time to replace batteries on the vehicle if it didn’t launch by June 6th. This process would involve rolling it off the pad and working on it. They highlighted that his process would take about 10 days but when combined with other tasks it could push the next launch opportunity a month or more away from the original date.

It’s important to point out that this mission is still considered an orbital flight test which the spacecraft has completed before however this time with two humans aboard. In particular, assuming complete mission success, this is the final test necessary in order for Boeing to certify the vehicle and begin routine flights to the International Space Station. NASA officials have said that Boeing needs to complete this certification by November or December to allow for the start of operational missions to the ISS. The first of those missions named Starliner 1, is already set to happen in early 2025. By now around 80% of the certification is complete with the last aspect relying on this launch and how it performs.

With this, a specific flight profile has been created to test both the human and spacecraft aspects of Starliner. This is Boeing’s second flight to the International Space Station and third Starliner flight test overall, following a second Orbital Flight Test, the uncrewed mission also known as OFT-2 in May 2022. Boeing also completed pad abort demonstration in November 2019.

When the vehicle does eventually launch from Space Launch Complex-41 and separate from ULA’s Atlas V rocket, Starliner will perform an engine burn to place the spacecraft and its crew into orbit for an approximately 24-hour journey to the space station. During the flight, the spacecraft and its crew will perform several flight test objectives, supporting the certification ahead of regular rotation missions for Starliner. The first test is to demonstrate performance of crew equipment from prelaunch through ascent, including suit and seat performance. During approach, rendezvous, and docking with the station, the Starliner team will assess spacecraft thruster performance for manual abort scenarios, conduct communication checkouts, test manual and automated navigation, and evaluate life support systems. Crew aboard the station will monitor the spacecraft’s approach and the Starliner crew would command any necessary aborts.

From there, Starliner will autonomously dock to the forward-facing port of the Harmony module. The test objective is to perform hatch opening and closing operations, configure the spacecraft for its time docked to the station, and transfer emergency equipment into the station. During its stay, the crew will evaluate the spacecraft, its displays, and cargo transfer systems. Wilmore and Williams will also go inside Starliner, close the hatch, and demonstrate the spacecraft can perform as a “safe haven” in the case one is needed in the future. Visiting spacecraft can be used as safe havens in the event of a contingency aboard the space station, such as depressurization, fire, or risk of collision with orbital debris.

They point out that Wilmore and Williams will live and work alongside the Expedition 71 crew for about a week before boarding Starliner for return to Earth. After undocking, the next flight test objective will assess manual piloting of Starliner before switching back to autonomous operations. The crew will spend approximately six hours in the spacecraft from undocking until its first landing opportunity. After touchdown, the crew aboard Starliner is responsible for jettisoning the parachutes, initiating spacecraft power down, and conducting a satellite phone call with the mission control landing and recovery teams. Following a landing and successful recovery, NASA will complete work to certify the spacecraft as an operational crew system for long-duration rotation missions to the space station, beginning with NASA’s Boeing Starliner-1.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, it was another scrub this morning for Starliner’s attempt to launch crew for the first time. This scrub had to do with the Ground Launch Sequencer not loading the correct operational configuration after proceeding into terminal count. We will have to wait and see how it progresses and the impact it has on the space industry.