Why NASA’s Space Launch System Could Be Replaced

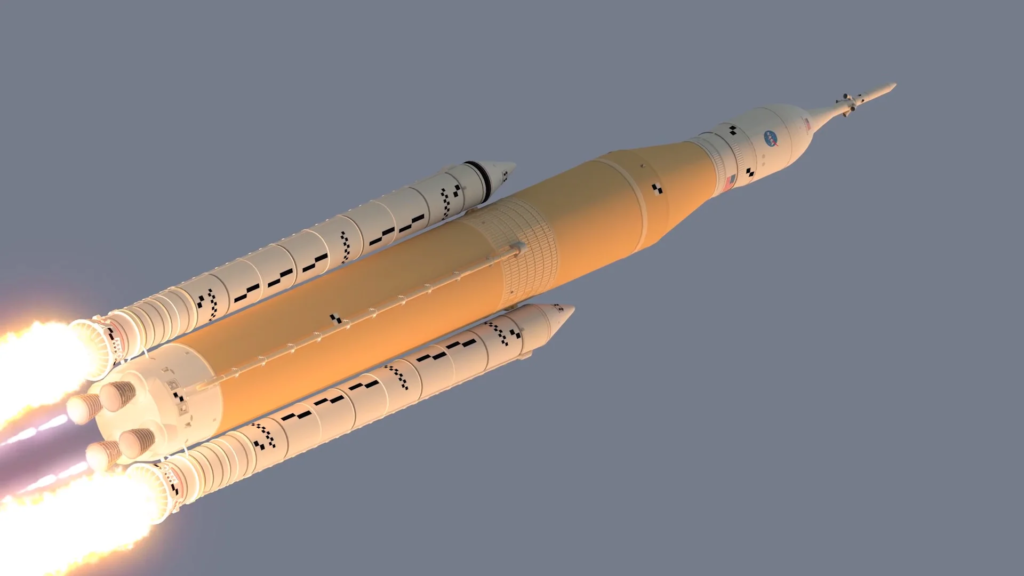

The Space Launch System rocket might not be the best option for NASA’s planned return to the Moon. A new 35-page report released just days ago by the agency’s OIG encourages NASA to look for possible replacements. This comes after continued schedule delays and cost increases, with no plan of slowing down.

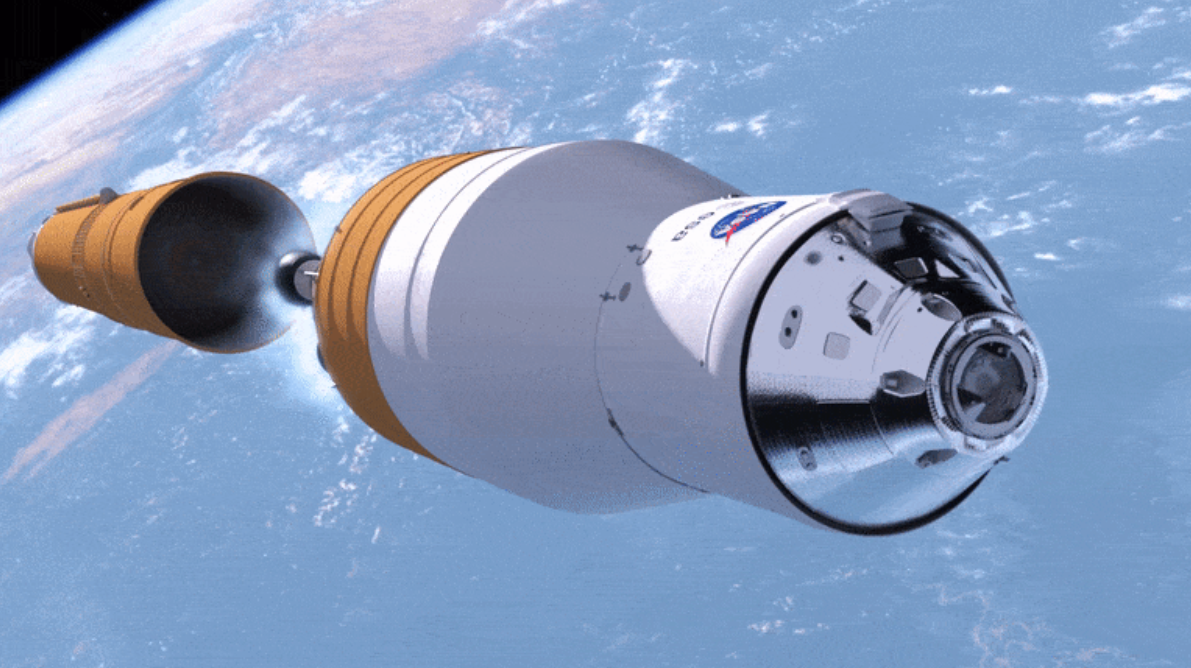

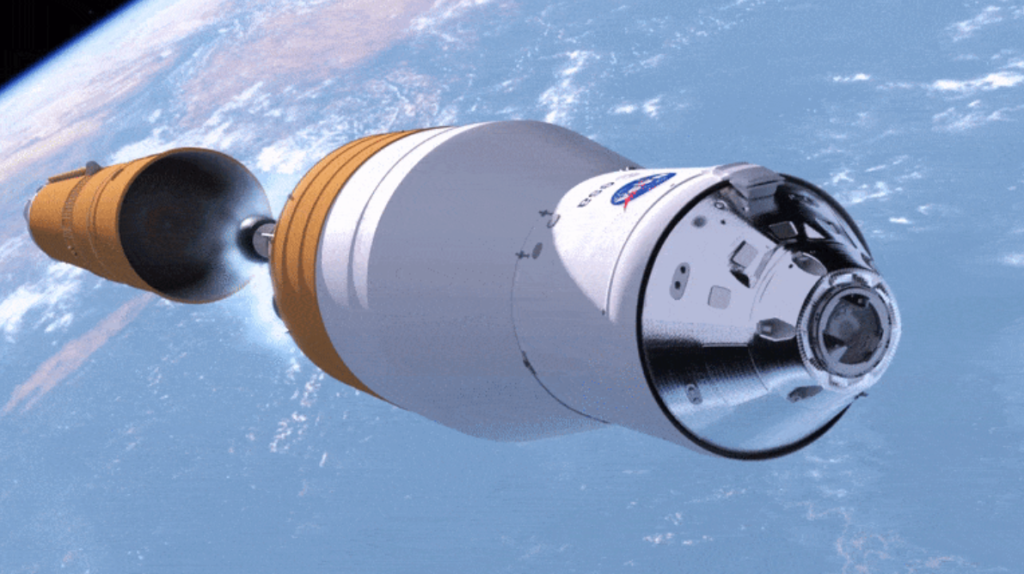

It’s important to point out that the Artemis program (responsible for returning humans to the Moon) is huge, and involves many missions. This in turn requires a lot of SLS rockets, even some upgraded versions as time goes on. The new agency audit however believes that it’s in NASA’s best interest to consider alternative options within the commercial industry, as they have begun to do with other missions and projects.

If not, they are concerned that the development of this rocket will only add more delays and increase mission costs in the long term. While companies within the commercial industry like SpaceX, could have a better option within that timeframe. Here I will go more in-depth into what this audit found, the current state of SLS, possible alternatives, and more.

New Agency Audit

Two days ago on October 12th, the NASA Office of Inspector General released a report titled, NASA’s Transition of the Space Launch System to a Commercial Services Contract. For context, the NASA Office of Inspector General or OIG, conducts audits, reviews, and investigations of NASA programs and operations to prevent and detect fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement and to assist NASA management in promoting economy, efficiency, and effectiveness.

They start off by highlighting that the SLS program accounts for about 1/4th of the total Artemis budget. They go on to say that “Given the enormous costs of the Artemis campaign, failure to achieve substantial

savings will significantly hinder the sustainability of NASA’s deep space human exploration efforts.” They also bring up some concerns in relation to a very large contract that the agency is preparing to sign. Specifically, NASA is getting ready to award a sole-sourced services contract, known as the Exploration Production and Operations Contract (EPOC), a newly formed joint venture of The Boeing Company and Northrop Grumman Systems Corporation—for the production, systems integration, and launch of at least 5 and up to 10 SLS flights beginning with Artemis V scheduled for 2029. Boeing and Northrop Grumman currently supply the SLS core and upper stages and boosters, respectively, that power the SLS.

In relation to this, the report then states, “Our analysis shows a single SLS Block 1B will cost at least $2.5 billion to produce—not including Systems Engineering and Integration costs—and NASA’s aspirational goal to achieve a cost savings of 50 percent is highly unrealistic. Specifically, our review determined that cost saving initiatives in several SLS production contracts such as reducing workforce within Boeing’s Stages contract and gaining manufacturing efficiencies with Aerojet Rocketdyne’s RS-25 Restart and Production Contract were not significant and, as a result, a single SLS will cost more than $2 billion through the first 10 SLS rockets produced under EPOC.

They counter this bad news with a suggestion highlighting, “Although the SLS is the only launch vehicle currently available that meets Artemis mission needs, in the next 3 to 5 years other human-rated commercial alternatives that are lighter, cheaper, and reusable may become available. Therefore, NASA may want to consider whether other commercial options should be a part of its mid- to long-term plans to support its ambitious space exploration goals.”

This is a very big deal and suggests a complete change to the future of the Artemis mission layout. Looking at a provided graphic, it shows the evolution of the SLS rocket and how many are meant to be built within the next decade. An open mind toward commercial options in the next few years could change what missions toward the end of the decade look like. However, even if there were reliable and more cost-effective options available in the future, it might not be in the best interest of some to switch from SLS. For example, the SLS program provides a lot of jobs in different parts of the country. A switch would also eliminate the majority of these positions which the agency and people making big decisions have to consider. At the same time, its possible commercial options in the future could be too good to turn down.

Possible Alternatives

Further in the audit, they talk more about the switch to commercial, and some of the options. In a statement, they say, “Expanding the SLS’s customer base beyond NASA’s human exploration efforts would have the potential to increase economies of scale due to larger material purchases and efficiencies with the workforce. In fact, studies conducted in preparation for the EPOC contract included independent assessments that estimated building a second SLS rocket each year would reduce costs, in one estimate, by one-third.

This being said, “despite Boeing’s intent to increase production and secure additional SLS customers to achieve its cost reduction targets, to date these efforts have been unsuccessful” they said. Funny enough, we have already see a few examples were SLS was meant to be used, but instead the payload was launched on a commercial rocket because it simply was cheaper. For example, the Department of Defense, specifically the Air Force and Space Force, have declined to use the SLS due to lower-cost alternatives with existing capabilities that meet their needs such as SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy and ULA’s Atlas V, as well as ULA’s forthcoming Vulcan Centaur rocket. Moreover, even though Congress initially directed NASA to use the SLS for the Science Mission Directorate’s Europa Clipper mission, NASA subsequently received congressional approval to use another launch vehicle and the Agency contracted with Space X for a Falcon Heavy rocket at a cost of $178 million.

They finish by saying, “In the near term, the SLS remains the only launch vehicle with the capability to lift the 27-metric ton Orion capsule to lunar orbit. However, in the next 3 to 5 years other human-rated commercial alternatives may become available. These commercial ventures will likely capitalize on multiple technological innovations, making them lighter, cheaper, and reusable. Further driving down costs is the competition between aerospace companies such as SpaceX, ULA, and Blue Origin, with both SpaceX and Blue Origin currently developing reusable medium- and heavy-lift launch vehicles that will compete with NASA’s SLS single-use rocket.

In this case, they are referring to Starship, which could easily meet the payload and cost requirements if it is up and running in 3 to 5 years from now. Currently, the rocket is awaiting FAA approval for the second test flight. The results of this test will have a direct effect on the future of the program and specifically the speed at which it reaches orbit. All this being said, it’s very possible Starship could be ready in around 4 years from now meaning NASA would have quite the option for a lot less money. You have to consider that if Starship was ready and proved itself as a reliable option, it would be hard to ignore the cost difference. The cost of Starship would be around a couple hundred million while SLS would be in the billions. Massive cost savings that are very hard to ignore no matter the downside.

Looking back at the report it says, “Although Congress directed NASA in 2010 to build a heavy-lift rocket and crew capsule using existing contracts from the canceled Constellation effort to meet its space exploration goals, the Agency may soon have more affordable commercial options to carry humans to the Moon and beyond. In our judgment, the Agency should continue to monitor the commercial development of heavy-lift space flight systems and begin discussions of whether it makes financial and strategic sense to consider these options as part of the Agency’s longer-term plans to support its ambitious space exploration goals.

In one final statement the audit points out, “To its credit, NASA has acknowledged the high costs of its Artemis goals—the SLS in particular—and since at least 2016 has been exploring ways to make the missions more affordable. The EPOC initiative is designed to transfer SLS production, integration, and launch to a Boeing-Northrop-Grumman joint venture known as DST using a commercial services construct. In our judgment, despite NASA’s noteworthy adjustments to the EPOC transition plan and its affordability initiatives, the price of the SLS Block 1B rockets will not be significantly reduced through such a sole-source contract with DST. NASA’s aspirational goal is to achieve a 50 percent cost savings over current SLS costs using DST, which by our calculation would reduce the contract cost of a single SLS rocket from the current $2.5 billion to $1.25 billion. Our analysis shows this goal realistically cannot be achieved and the production cost alone will remain over $2 billion” they said. For these reasons among others, we could see a commercial option in the future helping humans return to the Moon.

Finally, in the long term, commercial competition in launch services will be more practicable for the Agency to better leverage less costly commercial alternatives while achieving its mission goals. In the end, failure to significantly reduce the high costs of the SLS launch vehicle will significantly hinder the overall sustainability of the Artemis campaign and NASA’s deep space human exploration efforts. A warning from the OIG that something big needs to change between now and the end of the decade or else the Artemis program could end up in trouble.

Conclusion

NASA is continuing to try and lower SLS costs but the future outlook is not looking the best. A new audit from the NASA OIG pointed out a long list of changes including a focus on the commercial industry. We will have to wait and see how it progresses and the impact it has on the space industry.