What Exactly Went Wrong With Boeing’s Starliner?

Close to a decade ago, NASA began funding both SpaceX and Boeing with hopes to help facilitate a U.S. company to reach orbit. In the time since then, SpaceX has had a lot of success with the Dragon Spacecraft while Boeing on the other hand has struggled to keep up. With Starliner’s first crewed mission only months away, it brings up the question of what went wrong.

As of right now, Boeing’s Starliner has stacked up charges of around $900 million due to delays and various issues. This includes $410 million in 2020, $185 million in October 2021, and $288 million through the third quarter of last year. The program while still pushing forward, has continued to run into roadblocks and problems doing the company and spacecraft no favors.

Unfortunately for Boeing and Starliner, these issues are not only affecting current missions but also a lot of future opportunities. For comparison, Boeing’s commercial crew contract that NASA awarded in 2014 includes six post-certification missions. NASA awarded the same amount to SpaceX but has twice added missions to the contract, bringing the total to 14 as of right now. Here I will go more in-depth into Starliner’s history, what exactly went wrong, the future of the spacecraft, and more.

Rough Start

Besides initial delays, the first orbital test flight of Starliner did not go well. The uncrewed orbital flight test launched on December 20, 2019, but after deployment, an 11-hour offset in the mission clock of Starliner caused the spacecraft to compute that “it was in an orbital insertion burn”, when it was not. This caused the attitude control thrusters to consume more fuel than planned, precluding a docking with the International Space Station. The spacecraft landed at White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico, two days after launch.

Two software errors detected during the test, one of which prevented a planned docking with the International Space Station, could each have led to the destruction of the spacecraft, had they not been caught and corrected in time, NASA said on February 7, 2020. A joint NASA–Boeing investigation team found that “the two critical software defects were not detected ahead of flight despite multiple safeguards”, according to an agency statement. “Ground intervention prevented the loss of the vehicle in both cases”. Before re-entry, engineers discovered the second critical software error that affected the thruster firings needed to safely jettison the Starliner’s service module. The service module software error “incorrectly translated” the jettison thruster firing sequence. This initial launch failure came with a $410 million charge.

After these initial complications with OFT-1, the company began working toward OFT-2 with higher hopes. While this second uncrewed mission would eventually be successful, it took a lot longer than Boeing and NASA were hoping for. In 2021, Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner was within hours of launch on its second uncrewed test flight in early August when stuck valves in the spacecraft’s propulsion system forced a launch scrub that has turned into a delay that will extend well into next year. Specifically, during the August 2021 launch window, some issues were detected with 13 propulsion-system valves in the spacecraft prior to launch. The spacecraft had already been mated to its launch rocket, United Launch Alliance’s (ULA) Atlas V, and taken to the launchpad.

Attempts to fix the problem while on the launchpad failed, and the rocket was returned to the ULA’s VIF (Vertical Integration Facility). Attempts to fix the problem at the VIF also failed, and Boeing decided to return the spacecraft to the factory, thus canceling the launch at that launch window. To add to these issues, there was a commercial dispute between Boeing and Aerojet Rocketdyne over responsibility for fixing the problem. The valves had been corroded by the intrusion of moisture, which interacted with the propellant, but the source of the moisture was not apparent. By late September 2021, Boeing had not determined the root cause of the problem, and the flight was delayed indefinitely. In December 2021, Boeing decided to replace the entire service module and anticipated OFT-2 to occur in May 2022. This marked a major delay and another $185 million charge was added to the company’s total.

On the flight, two Orbital Maneuvering and Attitude Control System (OMACS) thrusters failed during the orbital insertion burn, but the spacecraft was able to compensate using the remaining OMACS thrusters with the addition of the Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters. A couple of RCS thrusters used to maneuver Starliner also failed during docking due to low chamber pressure. Some thermal systems used to cool the spacecraft showed extra cold temperatures, requiring engineers to manage it during the docking. While successful, it revealed that there was still a lot of work necessary, especially before humans got aboard.

Continued Delays

Now that we know more about Starliner’s first orbital test flights and what went wrong, we can take a closer look a the spacecraft itself and some of the additional delays. The last planned test flight is the crewed flight test. Although it had an original goal of 2017, various delays have pushed this back to no earlier than April 2023. The Crewed Flight Test will send a crew of two to the ISS for a short stay. This is the final test flight of Starliner, which will be cleared to begin operational flights after the results of this test are evaluated.

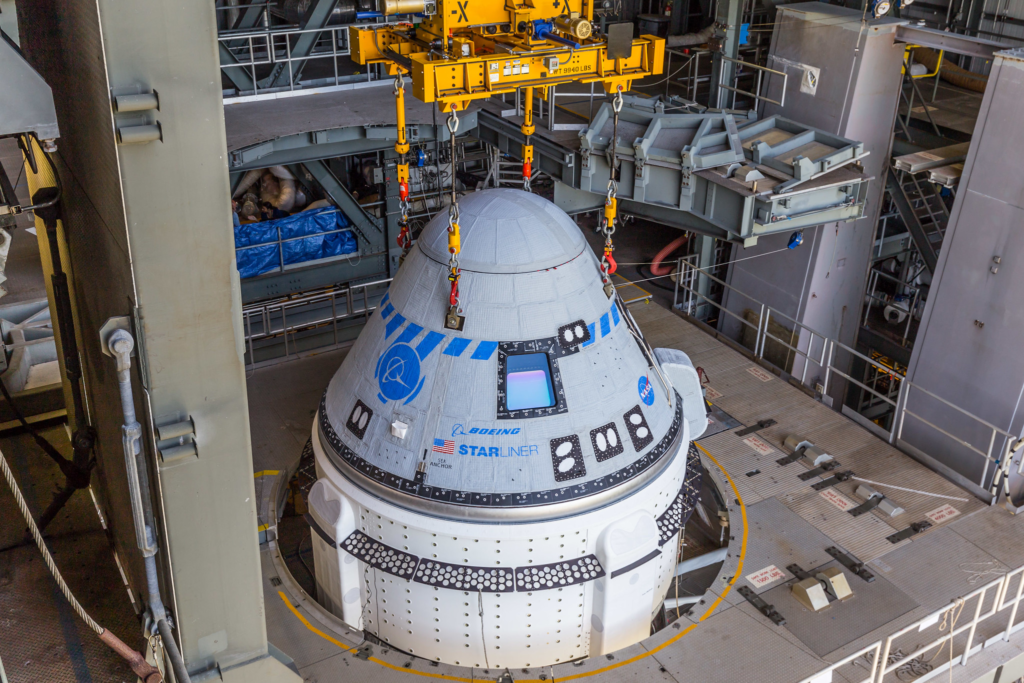

In terms of spacecraft design, Boeing’s Crew Space Transportation (CST)-100 Starliner spacecraft is being developed in collaboration with NASA’s Commercial Crew Program. The Starliner was designed to accommodate seven passengers, or a mix of crew and cargo, for missions to low-Earth orbit. For NASA service missions to the International Space Station, it will carry up to four NASA-sponsored crew members and time-critical scientific research. Boeing describes that the Starliner has an innovative, weldless structure and is reusable up to 10 times with a six-month turnaround time. It also features wireless internet and tablet technology for crew interfaces.

Back on September 16, 2014, NASA chose Boeing’s (Starliner) and SpaceX’s (Crew Dragon) as the two companies to be funded to develop systems to transport U.S. government crews to and from the International Space Station. Boeing won a US$4.2 billion contract to complete and certify the Starliner by 2017, while SpaceX won a US$2.6 billion contract to complete and certify their crewed Dragon spacecraft. The contracts include at least one crewed flight test with at least one NASA astronaut aboard. Once the Starliner achieves NASA certification, the contract requires Boeing to conduct at least two, and as many as six, crewed missions to the space station. At the time, NASA had considered the Starliner proposal as stronger than the Crew Dragon.

In May 2016, Boeing delayed its first scheduled Starliner launch from 2017 to early 2018. Then in October 2016, Boeing delayed its program by six months, from early 2018 to late 2018, following supplier holdups and a production problem on the Spacecraft. By 2016, they were hoping to fly NASA astronauts to the ISS by December 2018. In April 2018, NASA suggested that the first planned two-person flight of the Starliner, slated for November 2018, was now likely to occur in 2019 or 2020. If there are no further delays, it would be expected to carry one additional crew member and extra supplies. Instead of staying for two weeks, as originally planned, NASA said that the expanded crew could stay at the station for as long as six months as a normal rotational flight. As we know, now in 2023 Starliner has yet to carry astronauts into space.

As partially mentioned prior, not only have these issues caused a lot of charges to be stacked up, but it has also cost Boeing a lot of opportunities. In June of last year, NASA said it planned to buy five more crew rotation missions on SpaceX’s fleet of Dragon spaceships, bringing SpaceX’s contract with the space agency to 14 operational astronaut launches, likely enough to keep the International Space Station staffed through 2030. At the time in a statement, the agency said, “The five additional Dragon missions help ensure NASA maintains two independent crew transpiration providers, with SpaceX and Boeing alternating astronaut missions every six months once the agency certifies Boeing’s Starliner capsule for the job.” The main goal of NASA from the beginning was to have two different options for crew transport and some competition within the industry. This is meant to help facilitate innovation, lower costs, and make sure the agency always has an option for getting to and from space. While the Crew Dragon and SpaceX have been doing a great job, NASA has invested a lot in Boeing and still wants the company to succeed.

“Our goal has always been to have multiple providers for crewed transportation to the space station,” said Phil McAlister, director of commercial space at NASA, in a statement. “SpaceX has been reliably flying two NASA crewed missions per year, and now we must backfill those flights to help safely meet the agency’s long-term needs.”

Conclusion

Boeing has had a very rough few years developing, testing, and launching the Starliner spacecraft. After the first mission failed to rendezvous with the ISS, the second was delayed significantly. All of these problems have pushed back its first crewed mission and stacked up close to a billion dollars in charges. Hopefully later this year it successfully carries its crew to the ISS and back. We will have to wait and see how it progresses and the impact it has on the space industry.

NASA should dich Boeing and buy more dragons, Spacex is way cheaper