The Future of SLS & Returning Humans To The Moon

It has been far too long since the last time humans stepped foot on the Moon. This being said, NASA plans to change this not long from now apart of the Artemis missions. At the core of many of these future launches is the Space Launch System or SLS. In recent months this rocket has been very busy preparing for its first test flight expected to happen this summer.

Unfortunately, due to some complications during the wet dress rehearsal, this process has not yet been completed. However, NASA has been working to fix the different problems and recently provided updates on their progress. This is in addition to more details on what the future of the Space Launch System looks like and when we should expect to see it launch.

SLS is one of the most powerful rockets in the world with the important future responsibility of carrying crew and cargo to and from the Moon. This is why so much time and effort has gone into the prep and current tests such as the wet dress rehearsal. Here I will go more in-depth into the launch vehicle’s progress, when it will return to the pad, and what to expect in the near future.

Recent Updates

A complex rocket like the Space Launch System has many different parts and components that all need to work together in perfect harmony. In most cases, even if one aspect doesn’t work as intended, it can have a negative effect on the greater goal. This is something we recently saw in the wet dress rehearsal. In terms of current progress on the test, the Space Launch System and Orion spacecraft are slated to return to launch pad 39B at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida in early June for the next wet dress rehearsal attempt.

NASA pointed out that engineers successfully completed work on a number of items observed during the previous wet dress rehearsal test. This includes addressing the liquid hydrogen system leak at the tail service mast umbilical, replacing the interim cryogenic propulsion stage (ICPS) gaseous helium system check valve and support hardware, modifying the ICPS umbilical purge boots, and confirming there are no impacts to Orion as a result of storms and subsequent water intrusion at the launch pad. The team also updated software to address issues encountered during core stage tanking of liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen during previous rehearsal attempts. The purge boots are not flight hardware, but enclose an area around the ICPS umbilical. The interim cryogenic propulsion stage umbilical is located at about the 240-foot level on the mobile launcher tower. This umbilical supplies fuel, oxidizer, purge air, gaseous nitrogen and helium, and electrical connections to the interim cryogenic propulsion stage of the SLS rocket. The engine, just like the core stage engines, uses fuel (hydrogen) and oxidizer (oxygen) to create thrust. The umbilical also provides hazardous gas leak detection and swings away at launch.

Meanwhile, the contractor for gaseous nitrogen has completed their repairs to the distribution system that will be used to support the Artemis testing and launch campaign. The repairs and tests ensured the system is ready to support tanking operations. During wet dress rehearsal and launch, teams use gaseous nitrogen to purge the rocket including its umbilical plates, and to support other operations. Engineers also are completing some of the forward work originally scheduled to take place in the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) after wet dress rehearsal. This includes opening the Orion crew module hatch and installing some payloads, such as hardware elements for the Callisto technology demonstration, a flight kit locker, and container assemblies for a space biology experiment. Following completion of a few remaining verifications, teams will retract platforms inside the VAB to prepare SLS and Orion to roll out to pad 39B. Plans call for the next wet dress rehearsal to take place about 14 days after the rocket arrives at the pad.

Future of SLS

In addition to the recent updates regarding SLS and its progress towards finishing the wet dress rehearsal, NASA also gave updates on when we should expect to see SLS lift off for the first time apart of Artemis 1. Specifically, when Artemis I is ready to launch, a range of personnel from NASA, industry, and several international partners will be poised to support the mission. Before they get to launch day, the alignment of the Earth and Moon will determine when the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket with the uncrewed Orion spacecraft atop it can launch, along with several criteria for rocket and spacecraft performance. In order to determine potential launch dates, engineers identified key constraints required to accomplish the mission and keep the spacecraft safe. The resulting launch periods are the days or weeks when the spacecraft and rocket can meet mission objectives. These launch periods account for the complex orbital mechanics involved in launching on a precise trajectory toward the Moon while the Earth is rotating on its axis and the Moon is orbiting Earth each month in its lunar cycle. This results in a pattern of approximately two weeks of launch opportunities, followed by two weeks without launch opportunities.

NASA highlights that there are four primary parameters that dictate launch availability within these periods. These key constraints are unique to the Artemis I mission and future launch availability beyond this flight will be determined based on capabilities and trajectories unique to each mission. First, the launch day must account for the Moon’s position in its lunar cycle so that the SLS rocket’s upper stage can time the trans-lunar injection burn with enough performance to successfully intercept the “on ramp” for the lunar distant retrograde orbit. The more powerful Exploration Upper Stage on future configurations of the rocket will enable daily, or near-daily, launch opportunities to the Moon, depending on the orbit desired. Second, the resulting trajectory for a given day must ensure Orion is not in darkness for more than 90 minutes at a time so that the solar array wings can receive and convert sunlight to electricity and the spacecraft can maintain an optimal temperature range. Mission planners eliminate potential launch dates that would send Orion into extended eclipses during the flight. This constraint requires knowledge of the Earth, Moon, and Sun along the planned mission trajectory path before the mission ever occurs, as well as an understanding of the Orion spacecraft’s battery state of charge before entering an eclipse. Third, the launch date must support a trajectory that allows for the skip entry technique planned during Orion’s return to Earth. A skip entry is a maneuver in which the spacecraft dips into the upper part of Earth’s atmosphere and uses that atmosphere, along with the lift of the capsule, to simultaneously slow down and skip back out of the atmosphere, then reenter for final descent and splashdown. The technique allows engineers to pinpoint Orion’s splashdown location and on future missions will help lower the aerodynamic breaking loads astronauts inside the spacecraft will experience, and maintain the spacecraft’s structural loads within design limits. Lastly, the launch date must support daylight conditions for Orion’s splashdown to initially assist recovery personnel when they locate, secure, and retrieve the spacecraft from the Pacific Ocean.

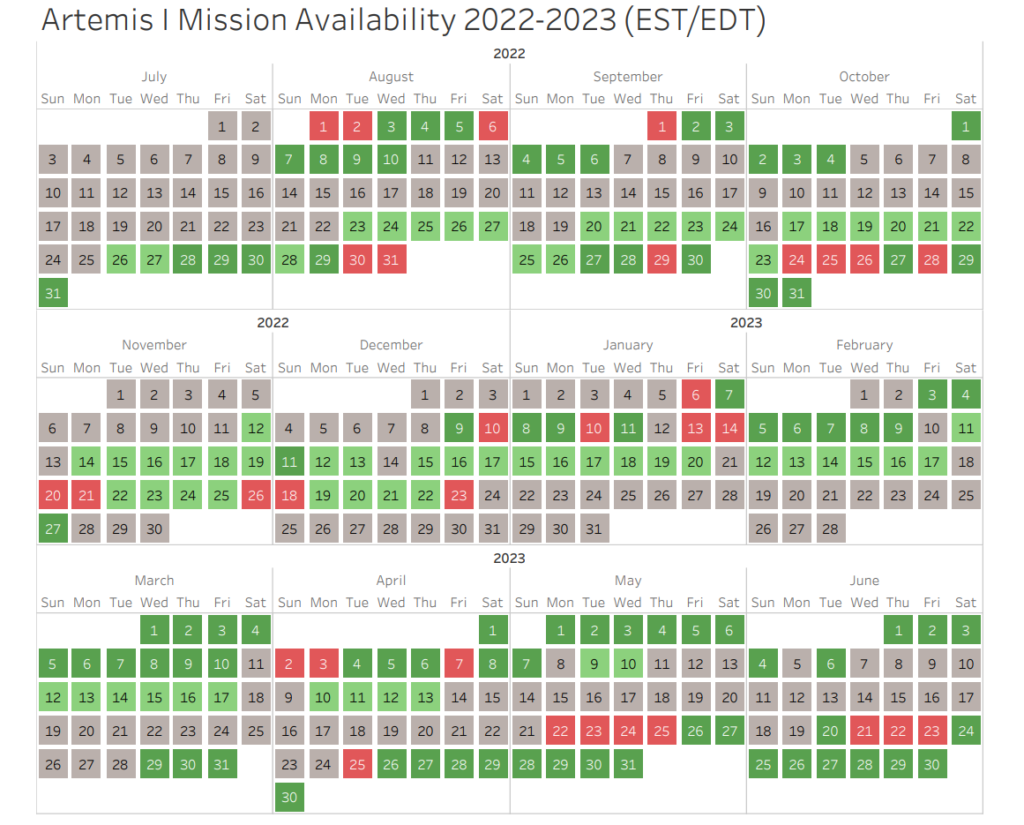

With all this being said, NASA has also released some specific dates we could expect to see SLS take off assuming everything goes according to plan. The earliest dates are from late July to early August. From here launch opportunities are off and on all the way to the end of 2022. Not only this but, the calendar also designates whether a launch on a particular date will be shorter in duration, of between 26 and 28 days, or longer in duration, of between 38 and 42 days. This is shown as dark green for long missions and light green for short missions on the calendar. The mission duration is varied by performing either a half lap or one and a half laps around the Moon in the distant retrograde orbit before returning to Earth and increases the number of days the mission can launch and meet the above constraints. Finally, there is an operational constraint driven by infrastructure at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Because of their size, the sphere-shaped tanks used to store cryogenic propellant at the launch pad can only supply a limited number of launch attempts depending on the type of propellant. Liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen are loaded in the rocket’s core stage and upper stage on the day of launch. Should the launch subsequently be called off, there is a minimum of 48 hours until a second launch attempt can be made. Another important factor NASA must consider.

Conclusion

Many of us have been watching closely as NASA continues to make progress toward returning humans to the Moon. At the core of many of these missions is the Space Launch System and Orion spacecraft. Right now these key systems are going through a series of tests to ensure they are ready for what’s to come. NASA also just released a thorough calendar for possible Artemis 1 launch dates. We will have to wait and see how it progresses and the impact it has on the space industry.