The Challenge of NASA’s Cost-Plus & Fixed Price Contracts

More and more over time, especially with big projects like Artemis underway, we are seeing NASA utilize the commercial industry for help. This involves paying companies to deliver certain hardware by a set date, at least that’s the idea. In reality, this process, especially depending on the contract type, can be very complicated with lots of delays.

The two most common contract types are cost-plus, and fixed-price contracts, both of which have certain pros and cons. To put in perspective the importance of this choice, and the debate it has caused, not long ago, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said that cost-plus contracts have been a plague on the agency. Responsible for both delays in project timelines and steep increases in cost.

On the other hand, other NASA officials have expressed the problem with fixed-price contracts and argued that they only save money but not time. With billions of dollars being spent on a long list of contracts, these decisions have a significant impact on the future of some of the agency’s most important missions. Here I will go more in-depth into the two contract types, NASA’s shift toward fixed-price, its effect on mission development, and more.

The Two Contracts

In reality, there are many more contract types than just cost plus and fixed. Some examples include cost-plus-award-fee (CPAF), cost-plus-incentive-fee (CPIF), firm-fixed price (FFP), cost-plus-fixed-fee, etc. However, they mainly fall into two different categories of simply cost plus or fixed price.

With this in mind, we can look at the main difference between the two. A cost-plus contract, is a contract such that a contractor is paid for all of its allowed expenses, plus additional payment to allow for a profit. A cost-type contract is often used for research and development efforts where technical requirements and specifications are very general, vague, uncertain or unknown, or circumstances do not allow the requiring organization to define its requirements sufficiently to allow for a fixed-price type contract, or uncertainties involved in contract performance do not permit costs to be estimated with sufficient accuracy to use any type of fixed-price contract.

This being said, there is limited certainty as to what the final cost will be. Often times additional funding is required or requested raising costs throughout the contract. It also requires additional oversight and administration to ensure that only permissible costs are paid and that the contractor is exercising adequate overall cost controls.

You then have fixed-price contracts. A fixed-price contract is a type of contract such that the payment amount does not depend on resources used or time expended by the contractor. Fixed prices can require more time, in advance, for sellers to determine the price of each item. However, the fixed-price items can each be purchased faster, but bargaining could set the price for an entire set of items being purchased, reducing the time for bulk purchases. In other words, NASA and the company agree on a timeframe and set amount, they pay them, and move on.

In regard to these different contract types, different NASA officials have very strong opinions as to which is best. For example, as partially mentioned prior, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson appearing before a US Senate Appropriations Subcommittee was quoted saying, “I believe that that is the plan that can bring us all the value of competition,” He said of fixed-price contracts. “You get it done with that competitive spirit. You get it done cheaper, and that allows us to move away from what has been a plague on us in the past, which is a cost-plus contract, and move to an existing contractual price.” He went on to say, “The old way to do things was always cost plus. And because of the competition that we’ve been talking about, we have been moving to the fixed price” he said.

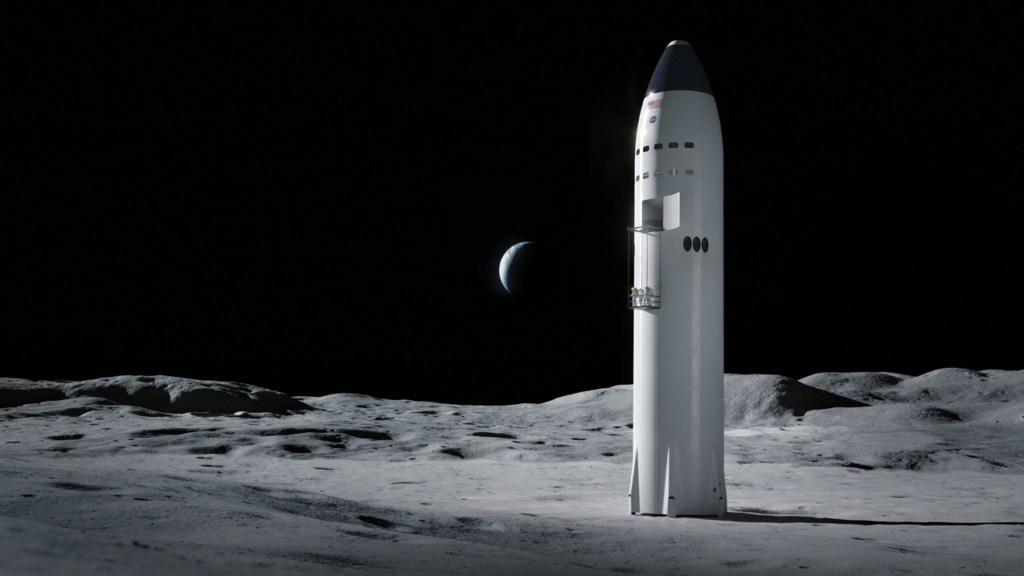

Although, not everyone at the agency agrees with this sentiment. Jim Free, the associate administrator at NASA recently talked about SpaceX and the issue with fixed-price contracts. For context, NASA awarded SpaceX a $2.9 billion fixed-price contract to develop a Starship lunar lander. Specifically, he was concerned about whether or not the company could meet its deadline. He commented “They have a significant number of launches to go, and that, of course, gives me concern about the December of 2025 date” for Artemis III. “With the difficulties that SpaceX has had, I think that’s really concerning. You can think about that slipping probably into ’26” he said.

In relation to this, he went on to talk about the contract type for this hardware saying, “The fact is, if they’re not flying on the time they’ve said, it does us no good to have a firm, fixed-price contract other than we’re not paying more.”

High Contract Prices

Based on this information and agency opinions, we can now look at actual current contracts and some of the results. The Space Launch System or SLS Rocket is a great example as a bunch of different companies are all contracted to produce its different hardware and components.

All the way back around 2015 NASA awarded Aerojet Rocketdyne a combined total of $5.7 billion apart of a Restart and Production program, meant to upgrade and produce a certain amount of engines. To be specific, NASA initially awarded the company $2.1 billion under a program named “Adaptation” between June 2006 to September 2020, and $3.6 billion for the Restart and Production program, from November 2015 to September 2029. This was for the RS-25 engine which SLS uses four of on the first stage. In May, a full report titled “NASA’s Management of The Space Launch System Booster and Engine Contracts” was released. This report was completed by the Office of Inspector General which commonly comes out with information and is critical of the agency as necessary.

In the new audit, they examined the extent to which NASA is meeting cost, schedule, and performance goals for the Boosters and Adaptation contracts, and whether the RS-25 Restart and Production, the follow-on production contracts, reduce the government’s financial risk and promote affordability. In short, they don’t. In the very first sentence, they say “NASA continues to experience significant scope growth, cost increases, and schedule delays on its booster and RS-25 engine contracts, resulting in approximately $6 billion in cost increases and over 6 years in schedule delays above NASA’s original projections.

These increases are caused by long-standing, interrelated issues such as assumptions that the use of heritage technologies from the Space Shuttle and Constellation Programs were expected to result in significant cost and schedule savings compared to developing new systems for the SLS. However, the complexity of developing, updating, and integrating new systems along with heritage components proved to be much greater than anticipated, resulting in the completion of only 5 of 16 engines under the Adaptation contract. They continued by saying, “While NASA requirements and best practices emphasize that technology development and design work should be completed before the start of production activities, the Agency is concurrently developing and producing both its engines and boosters, increasing the risk of additional cost and schedule increases.

The audit went on to say “Further, NASA used cost-plus contracts at times where we believe fixed-price contracts should have been considered to potentially reduce costs, including the addition of 18 new production engines under the RS-25 Restart and Production contract. In addition, contractors did not receive accurate performance ratings in accordance with federal requirements, such as the “very good” rating awarded to Aerojet Rocketdyne on the end-item Adaptation contract despite only finishing 5 of 16 engines. As a result, we question $19.8 million in award fees it received for the 11 unfinished engines which were subsequently moved to the RS-25 Restart and Production contract and may now be eligible to receive additional award fees.”

Looking even further, the audit determined that award fee percentages are inflated for Cost-Plus Production Contracts. In another quote they say, “We found that the negotiated award fee percentage of costs for the RS-25 Restart and Production contract is higher than typically found in contracts of this type. While the award fee percentage for cost-plus production contracts could be as low as a 6 to 8 percent range, the RS-25 Restart and Production contract award fee is in the 10 to 13 percent range. According to Engines Element officials, the range targeted was benchmarked to the prior Adaptation contract’s rate and “is typical for high-risk, high-value, high-complexity, human space flight program contracts.” However, unlike the Adaptation contract, the follow-on contract is for certification of the RS-25 redesign production of new engines and leverages the matured RS-25 design. Given the maturity of the RS-25 engine design and the use of cost-plus CLINs, we question whether a lower target percentage should have been negotiated” they said.

It’s clear based on all this information that the agency’s recent shift favoring fixed price contracts is based on past results, or a lack thereof. At the same time, even fixed-price contracts aren’t perfect, and often end with delays. It seems that cost-plus contracts usually cost more money and are delayed, while fixed price are just delayed.

Conclusion

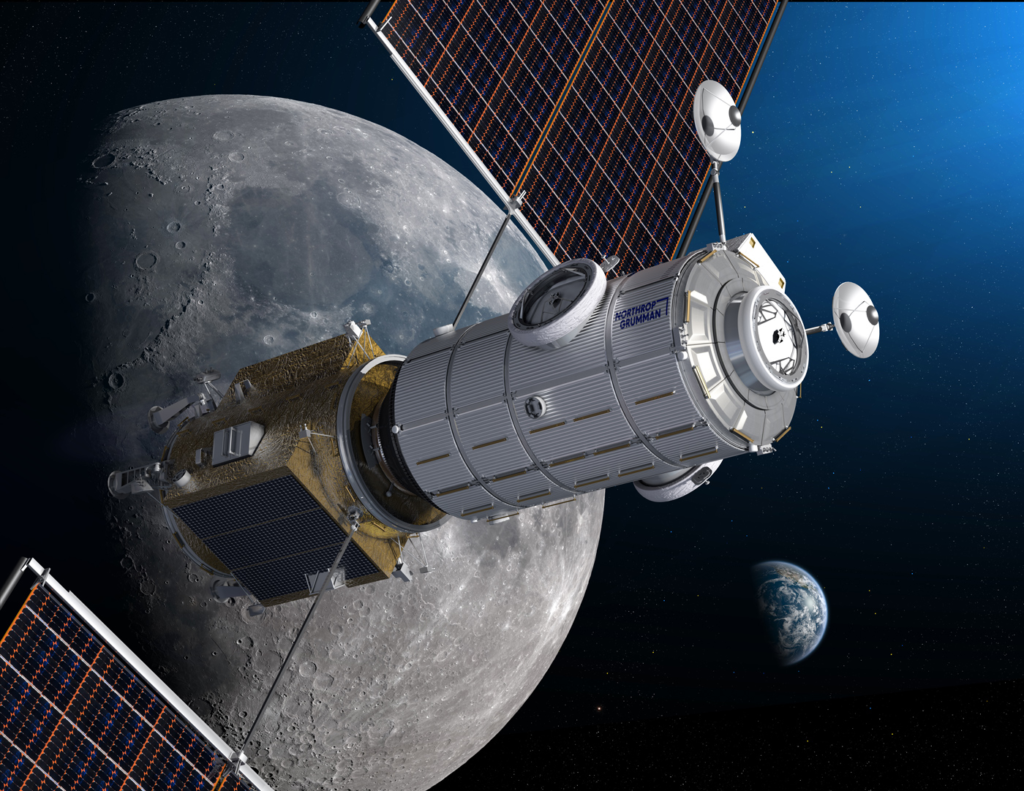

NASA is in the process of trying to return to the Moon, and is using the commercial industry for help. This involves multiple billion-dollar contracts, which there are many different types of, some better than others. We will have to wait and see how it progresses and the impact it has on the space industry.