New SLS Rollout Date, Repair Updates, & More

The Space Launch System has been trying to lift off for multiple months now. Unfortunately, a long list of complications have come in the way including weather, liquid hydrogen leaks, and much more. By now the next generation launch vehicle has made the trip to and from the Vehicle Assembly Building quite a few times. A pattern NASA is hoping to change in the coming weeks.

Just yesterday the agency released more information on the upcoming launch, rollout dates, final repairs, and more. Specifically, as of right now, NASA is planning to roll SLS back out to the pad on November 4th. This comes after the rocket was sent back to the VAB for a few repairs, required work on the flight termination system, and to avoid hurricane Ian.

All of which in hopes that for the first time the Space Launch System can lift off a part of the Artemis 1 mission and begin the long process of returning humans to the surface of the Moon. In reality, the longer this initial mission takes, the longer before this milestone is reached by the agency. Here I will go more in-depth into the recent updates, next week’s rollout, what to expect, and more.

Rollout Soon

Currently, teams are on track to roll the Space Launch System rocket and Orion spacecraft from the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) to Launch Pad 39B no earlier than Friday, Nov. 4 with the first motion targeted for 12:01 a.m. EDT. Just yesterday NASA tweeted saying, “Platform F is now the only platform left surrounding @NASA_SLS and @NASA_Orion in the Vehicle Assembly Building at @NASAKennedy. The vehicle is undergoing final preparations for its roll out to Pad 39B, for a launch to the Moon on #Artemis I, as early as Nov. 14.”

In the last couple of weeks, the agency has been very busy with work on the rocket in preparation for the next launch attempt. By now, minor repairs identified through detailed inspections are mostly completed. Preparations are underway to ready the mobile launcher and VAB for rollout by configuring the mobile launcher arms and umbilicals and continuing to retract the access platforms surrounding SLS and Orion as work is completed. In addition, testing of the reaction control system on the twin solid rocket boosters, as well as the installation of the flight batteries, is complete and those components are ready for flight. Engineers also have replaced the batteries on the interim cryogenic propulsion stage (ICPS), which was powered up for a series of tests to ensure the stage is functioning properly. Teams successfully completed final confidence checks for the ICPS, launch vehicle stage adapter, and the core stage forward skirt.

Teams are also continuing to work in the intertank area of the core stage and upper section of the boosters to replace batteries. These areas will remain open to support remaining battery and flight termination system activities. Flight termination system testing will start next week on the intertank and booster and once complete, those elements will be ready for launch. However, charging of the secondary payloads in the Orion stage adapter is complete. Teams recharged, replaced, and reinstalled several of the radiation instruments and the crew seat accelerometer inside Orion ahead of the crew module closure for roll. For example, radiation sensor technology aboard the spacecraft includes six Radiation Area Monitor (RAM) passive detectors about the size of a matchbox that will record the total radiation dose during the mission. As passive instruments, they require no source of power to collect radiation dose information and will be analyzed after the flight. Technicians will refresh the specimens for the space biology payload at the launch pad. The crew module and launch abort system hatches are closed for the roll to the pad, and engineers will perform final closeouts at the pad prior to launch.

Teams will plan to move the crawler transporter into position outside of the VAB ahead of rolling into the facility early next week. The agency continues to target a launch date no earlier than Nov. 14 at 12:07 a.m. EDT.

Launch Date & Overview

Now that we know more about what NASA and the teams have been working on while in the VAB, we can take a closer look at the launch date, launch periods, and the mission itself. As we know the agency is officially aiming for November 14th as the next launch date. This date falls within the November launch period that goes from November 12th to November 27th, with four exceptions within that period. These specific dates account for specific maneuvers, access to light during Orion’s trip, time of day when Orion returns, and the Moon’s position. If the launch were to be delayed past the 27th, NASA’s next opportunity to launch SLS would have to wait till around mid December. Specifically, the next launch period goes from December 9th to the 23rd.

All of which apart of Artemis I, formerly Exploration Mission-1, the first integrated test of NASA’s deep space exploration systems: the Orion spacecraft, Space Launch System (SLS) rocket, and the ground systems at Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida. The importance of this mission is both part of the reason for many of the delays and also why they are so crucial to avoid. As the first launch in a series of increasingly complex missions, Artemis I will be an uncrewed flight test that will provide a foundation for human deep space exploration, and demonstrate our commitment and capability to extend human existence to the Moon and beyond.

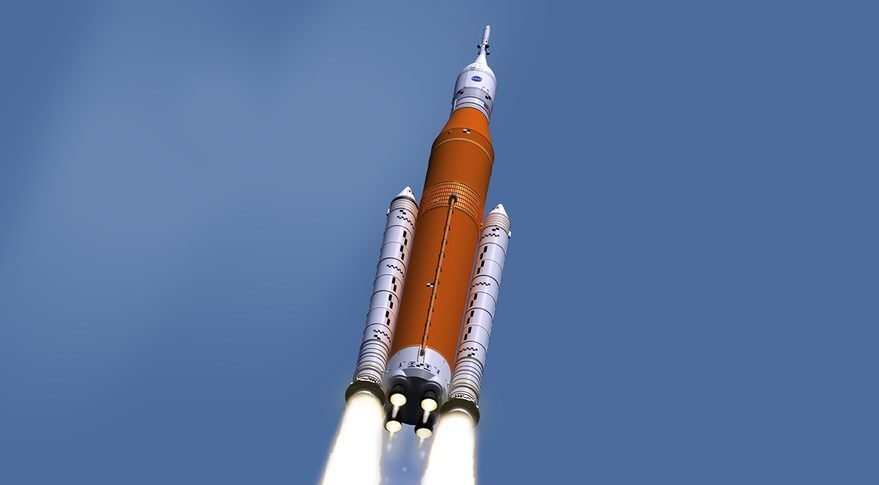

It beings as SLS and Orion will blast off from Launch Complex 39B at NASA’s modernized spaceport at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The SLS rocket is designed for missions beyond low-Earth orbit carrying crew or cargo to the Moon and beyond, and will produce 8.8 million pounds of thrust during liftoff and ascent to loft a vehicle weighing nearly six million pounds to orbit. Propelled by a pair of five segment boosters and four RS-25 engines, the rocket will reach the period of greatest atmospheric force within ninety seconds. After jettisoning the boosters, service module panels, and launch abort system, the core stage engines will shut down and the core stage will separate from the spacecraft. As the spacecraft makes an orbit of Earth, it will deploy its solar arrays and the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (ICPS) will give Orion the big push needed to leave Earth’s orbit and travel toward the Moon. From there, Orion will separate from the ICPS within about two hours after launch. The ICPS will then deploy a number of small satellites, known as CubeSats, to perform several experiments and technology demonstrations.

As Orion continues on its path from Earth orbit to the Moon, it will be propelled by a service module provided by the European Space Agency, which will supply the spacecraft’s main propulsion system and power (as well as house air and water for astronauts on future missions). Orion will pass through the Van Allen radiation belts, fly past the Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite constellation, and above communication satellites in Earth orbit. To talk with mission control in Houston, Orion will switch from NASA’s Tracking and Data Relay Satellites system and communicate through the Deep Space Network. From here, Orion will continue to demonstrate its unique design to navigate, communicate, and operate in a deep space environment. The outbound trip to the Moon will take several days, during which time engineers will evaluate the spacecraft’s systems and, as needed, correct its trajectory. Orion will fly about 62 miles (100 km) above the surface of the Moon, and then use the Moon’s gravitational force to propel Orion into a new deep retrograde, or opposite, orbit about 40,000 miles (70,000 km) from the Moon. The spacecraft will stay in that orbit for approximately six days to collect data and allow mission controllers to assess the performance of the spacecraft. During this period, Orion will travel in a direction around the Moon retrograde from the direction the Moon travels around Earth.

Finally, for its return trip to Earth, Orion will do another close flyby that takes the spacecraft within about 60 miles of the Moon’s surface, the spacecraft will use another precisely timed engine firing of the European-provided service module in conjunction with the Moon’s gravity to accelerate back toward Earth. This maneuver will set the spacecraft on its trajectory back toward Earth to enter our planet’s atmosphere traveling at 25,000 mph (11 kilometers per second), producing temperatures of approximately 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit (2,760 degrees Celsius) – faster and hotter than Orion experienced during its 2014 flight test. After about four to six weeks and a total distance traveled exceeding 1.3 million miles, the mission will end with a test of Orion’s capability to return safely to the Earth as the spacecraft makes a precision landing within eyesight of the recovery ship off the coast of Baja, California. Following splashdown, Orion will remain powered for a period of time as divers from the U.S. Navy and operations teams from NASA’s Exploration Ground Systems approach in small boats from the waiting recovery ship. If successful, this will mark a major milestone for Artemis and help lead to the future missions with humans on board such as Artemis II and III.

Conclusion

NASA has been busy over the past few weeks finishing some of the final preparations for another Space Launch System rollout. This included some small repairs, battery charging, and more. With practically everything done, the rocket is set to return to the pad in just a few days from now in early November. We will have to wait and see how it progresses and the impact it has on the space industry.