NASA’s Difficult Transition From The ISS To Private Stations

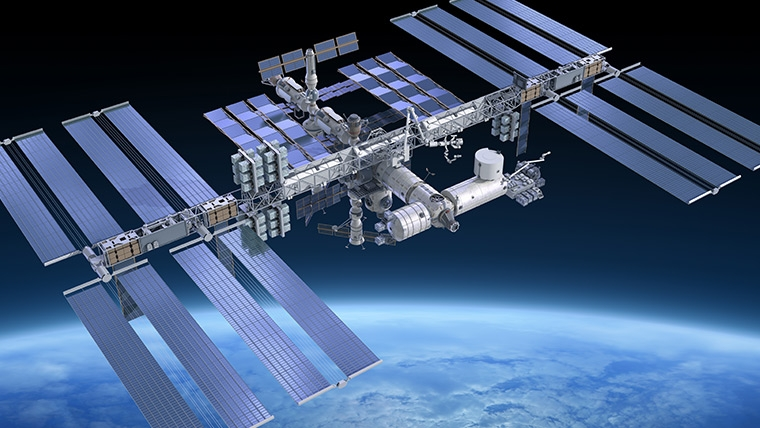

The International Space Station is approaching its final years of operation. For over two decades, the orbiting laboratory has been providing access to a unique environment that facilitates one-of-a-kind tests and experiments. However, as technology continues to advance, and NASA starts working on missions to the Moon and beyond, the need for a space station in LEO only grows.

For quite a long time now, NASA has been planning to retire the station in 2030 and get commercial options up and running before then. While this sounds like a great plan, recent comments from agency officials suggest that they are starting to run out of time. This is not good as the retirement date will likely stay the same putting extra pressure on companies like Axiom Space.

Not only this, but in order for the transition to be seamless, commercial options need to be ready not by 2030 but by 2028 allowing two years of leeway. Here I will go more in-depth into the process of retiring the ISS, schedule concerns, when Axiom Station will be ready, and more.

Tight Deadline

Early last year NASA confirmed that they planned to extend space station operations until 2030 in order to enable the United States to continue to reap these benefits of the station for the next decade. In addition to NASA, the other ISS partners include Japan, Canada and the European Space Agency (ESA) which also have committed to support the ISS until its phased retirement operation planned for 2030. Russia on the other hand, confirmed its support only until 2028, however, after which it will focus on building its own orbital space station, whose first module is expected to launch in 2027.

Even though this has been the plan for a while, NASA is still trying to figure out the transition process toward the end of the station’s life. In regard to this, ISS director Robyn Gatens, during a panel discussion at the ISS Research and Development Conference earlier this month said, “The reason this is so important is because we do believe that the impact of a gap will be disruptive,” NASA has previously discussed having roughly a two-year period, which would require at least one commercial station in service by 2028 to enable an ISS retirement in 2030. “It’s undefined right now,” Montalbano said of that transition. “We’re getting inputs from our partners. We want to figure out what’s going to be helpful, what’s not going to be helpful.”

With this 2028 deadline in mind, we can focus on commercial space station progress and see where the problem becomes evident. While there are a few future commercial options in the works, NASA’s main focus and the station that will attach to the ISS is Axiom Station. Back in 2020 the agency and company agreed to work together and allow Axiom to connect its own station modules to the ISS. This allows the station to operate before its complete, relying on ISS power and other resources at first. It then would disconnect once complete before the ISS retires. Looking at future dates, however, brings up a few concerns.

The first Axiom module is set to launch in 2025. Over the next few years, more modules will lift off including Hab Two and the Research and Manufacturing Facility in 2026, and even the observatory. The final piece that will complete the station is the power thermal module, scheduled to lift off no earlier than 2027. This timeline is slightly concerning considering the 2028 deadline to start ISS transition activities.

It’s also important to point out that because commercial space station services are still an unproven market, creating a seamless transition is not going to be easy. For example, experts will need to worry about things like technical costs and scheduling risks in terms of design and development of the space station platforms. The Boeing program manager for the ISS program, said at the conference. “They will get there but it will not be easy.” To add to this, with a vast majority of the research on the ISS funded by the federal government, and the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 suspending the debt ceiling until the end of 2024, “we will be faced with difficult budget cycles in the near future,” he said.

Lastly, the director of strategy and business development at Northrop Grumman Space Systems, said another issue is how international partners will participate on commercial stations. “We do need NASA and the government’s help on that.” He also cited regulatory and liability uncertainties for commercial space stations that need to be worked out. “We’ll get there, eventually,” he said, “but my biggest concern is that we have to get there in a reasonable amount of time. We cannot have a gap in low Earth orbit.”

ISS Retirement

Today, with U.S. commercial crew and cargo transportation systems online, the station is busier than ever. The ISS National Laboratory, responsible for utilizing 50 percent of NASA’s resources aboard the space station, hosts hundreds of experiments from other government agencies, academia, and commercial users to return benefits to people and industry on the ground. Meanwhile, NASA’s research and development activities aboard are advancing the technologies and procedures that will be necessary to send humans back to the Moon.

“The private sector is technically and financially capable of developing and operating commercial low-Earth orbit destinations, with NASA’s assistance. We look forward to sharing our lessons learned and operations experience with the private sector to help them develop safe, reliable, and cost-effective destinations in space,” said Phil McAlister, director of commercial space at NASA Headquarters. “The report we have delivered to Congress describes, in detail, our comprehensive plan for ensuring a smooth transition to commercial destinations after retirement of the International Space Station in 2030,” he said.

Looking at this plan, deorbiting the station will be quite the process, and not cheap either. Originally, the plan involved using available ISS maneuvering and a Russian Progress spacecraft. Specifically, in the nominal scenario, ISS mission control would begin scheduling retrograde ISS maneuvers in the lead-up to ISS deorbit to begin slowly lowering the operational altitude of the ISS. These retrograde maneuvers were planned to start at different times depending on solar cycle activity and its effect on Earth’s atmosphere (higher solar activity tends to expand the Earth’s atmosphere and increase resistance to the ISS’ velocity, resulting in more drag and natural altitude loss).

This lower altitude would result in higher velocity overall. Eventually, after performing maneuvers to line up the final target ground track and debris footprint over the South Pacific Oceanic Uninhabited Area (SPOUA), the area around Point Nemo, ISS operators would perform the ISS re-entry burn, providing the final push to lower ISS as much as possible and ensure safe atmospheric entry.

Earlier this year however we learned that NASA now plans to spend up to $1 billion on a tug to deorbit the ISS. Specifically, NASA is seeking $180 million in 2024 to start work on the tug, and anticipates spending as much as $1 billion to build it. As partially mentioned prior, the agency had earlier plans to use cargo spacecraft, particularly Russia’s Progress, to deorbit the station. In its request for information last year, the agency said it concluded “additional spacecraft may provide more robust capabilities for deorbit” and decided to ask the industry for its concepts.

“We’re always looking for redundancy,” Lueders said, with NASA continuing to work with Roscosmos on using Progress vehicles for deorbiting. “We are also developing this U.S. capability as a way to have redundancy and be able to better aid the targeting of the vehicle and the safe return of the vehicle, especially as we’re adding more modules” she said.

NASA then said that it anticipated launching the deorbit vehicle about one year before reentry, docking to the forward port of the station’s Harmony module. The vehicle would primarily operate during the final days before reentry, once the station’s orbit has decayed to an altitude of 220 kilometers. The vehicle would perform one or more “shaping” burns to lower the orbit’s perigee to 160 kilometers, followed by a final deorbit burn.

Earlier, NASA was considering options to procure the deorbit vehicle as a service. However, NASA now intends to take ownership of the deorbit vehicle and manage its operations. NASA will separately procure a medium-class launch of the deorbit vehicle. Some within the industry see the proposed deorbit vehicle as an opportunity to develop or demonstrate commercial systems for deorbiting or servicing spacecraft. However, the decision not to pursue a services approach, as well as specific technical requirements for deorbiting the ISS such as the ability to operate even after suffering two failures, made that less feasible.

The overall process is not ideal. The ISS costs a lot of money to keep running each and every year but it also provides some incredible utility. At the same time, it will cost the agency a lot of time and money just to develop the vehicle needed to safely deorbit the station into the ocean. A process we will likely hear more about over the next few years.

Conclusion

NASA is a bit concerned that they don’t have enough time before ISS retirement to properly transition to commercial options. Stations like Axiom station are expected to finish right at the time when the ISS is about to retire. We will have to wait and see how it progresses and the impact it has on the space industry.