Yesterday afternoon we got news that NASA has picked SpaceX and the Falcon Heavy in particular to launch a nuclear-powered drone to Saturn’s Moon Titan. The firm-fixed-price contract has a value of approximately $256.6 million.

Scheduled to launch in 2028, this rotorcraft named Dragonfly will sample materials and determine surface composition in different geologic settings, advancing our search for the building blocks of life. The contract award comes not long after the successful launch of Europa Clipper.

New Contract

Yesterday both SpaceX and NASA announced the new contract and included some details about the mission. SpaceX tweeted saying, “Falcon Heavy was selected by NASA to launch the Dragonfly mission to Saturn’s moon Titan!”

The contract value of over $256 million, includes launch services and other mission-related costs. In an official statement, they clarified, “The Dragonfly mission currently has a targeted launch period from July 5, 2028, to July 25, 2028, on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket from Launch Complex 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.”

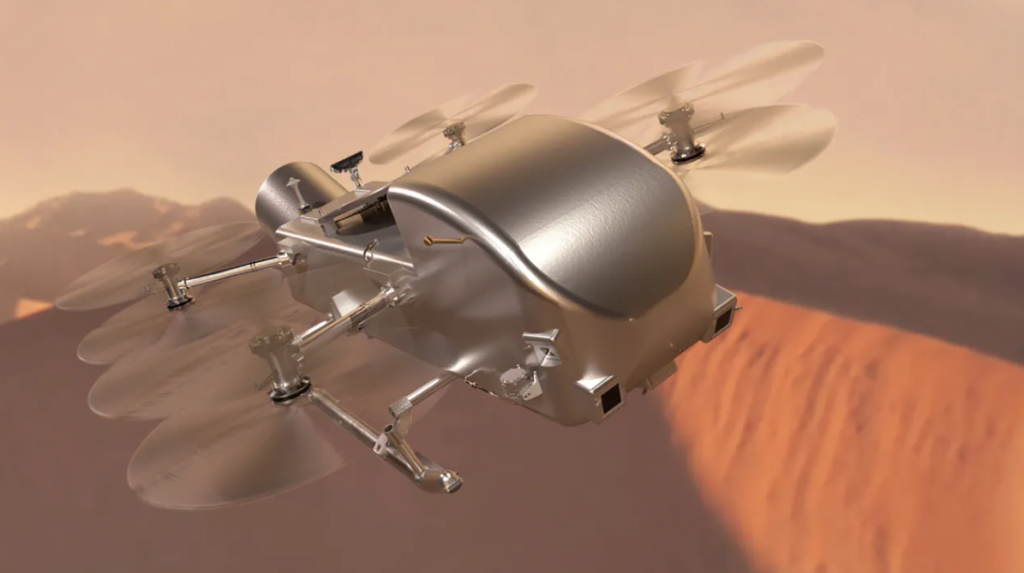

As for the payload itself, “Dragonfly centers on a novel approach to planetary exploration, employing a rotorcraft-lander to travel between and sample diverse sites on Saturn’s largest moon. With contributions from partners around the globe, Dragonfly’s scientific payload will characterize the habitability of Titan’s environment, investigate the progression of prebiotic chemistry on Titan, where carbon-rich material and liquid water may have mixed for an extended period, and search for chemical indications of whether water-based or hydrocarbon-based life once existed on Saturn’s moon.”

As far as why the use of a Falcon Heavy rocket is necessary, it’s a combination of payload size and especially distance. To put it in perspective, “The Dragonfly rotorcraft lander is no ordinary drone. Weighing about 1,900 pounds (875 kilograms), Dragonfly will be about 12.5 feet (3.85 meters) long, 12.5 feet (3.85 meters) wide and more than 5.5 feet (1.75 meters) tall, carried by eight sets of rotors. The Dragonfly body consists of aluminum panels and interior decks as well as aluminum honeycomb fuselage skin.

Contributing to the weight and size, it’s powered by a battery and a Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (MMRTG). Heat from the MMRTG will also enable conductive thermal control on the way to Titan, and convective thermal control when Dragonfly operates at Titan. Despite a launch date in 2028, it’s not expected to arrive at Saturn’s Moon until about 6 years later around 2034.

In terms of the decision to pick Falcon Heavy as opposed to other launch providers, it likely came down to its launch record. While there are some other promising options either just about to start launching or which have a few missions under their belt, such as New Glenn or Vulcan, the Falcon Heavy now has a pretty extensive launch history.

This includes 11 successful launches with the most recent being the Europa Clipper mission. Similar to the new Dragonfly contract, that mission was a very big and expensive payload heading hundreds of millions of miles away. Also on that flight, the Falcon Heavy was fully expendable as both the side boosters and core were expended without landing legs and grid fins. Not to mention, between now and the launch date in 2028, we can expect the Falcon Heavy to have launched another 10-plus times.

Focusing back on the contract, the awarded price of over $256 million is quite high compared to other agency-related Falcon Heavy missions in the past. It’s assumed that the fact that this mission involves an RTG that needs to be integrated into the payload fairings and dealt with has added to the mission price. For comparison, Europa Clipper’s price was $178 million and Psyche was $117 million.

Over the next few months and years, we can expect even more updates on Dragonfly and once we get closer to the launch date, updates on the Falcon Heavy and its mission. By far this mission is one of NASA’s most ambitious and features some very unique mission goals assuming everything goes as planned. Something to look forward to in the future.

Dragonfly On Titan

The rotorcraft will fly to dozens of promising locations on Titan looking for prebiotic chemical processes common on both Titan and Earth. Dragonfly marks the first time NASA will fly a multi-rotor vehicle for science on another planet; it has eight rotors and flies like a large drone. It will take advantage of Titan’s dense atmosphere – four times denser than Earth’s – to become the first vehicle ever to fly its entire science payload to new places for repeatable and targeted access to surface materials.

The agency highlights that “Titan is an analog to the very early Earth, and can provide clues to how life may have arisen on our planet. During its 2.7-year baseline mission, Dragonfly will explore diverse environments from organic dunes to the floor of an impact crater where liquid water and complex organic materials key to life once existed together for possibly tens of thousands of years. Its instruments will study how far prebiotic chemistry may have progressed. They also will investigate the moon’s atmospheric and surface properties and its subsurface ocean and liquid reservoirs. Additionally, instruments will search for chemical evidence of past or extant life.”

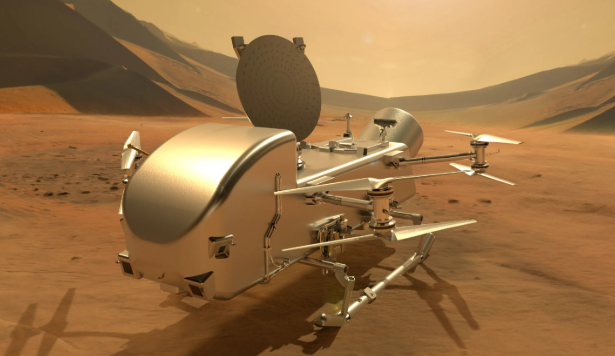

One of the most important mission milestones will be actually landing on the Moon. In this case, Dragonfly took advantage of 13 years’ worth of Cassini data to choose a calm weather period to land, along with a safe initial landing site and scientifically interesting targets. It will first land at the equatorial dune fields, which offer a diverse sampling location. Dragonfly will explore this region in short flights, building up to a series of longer “leapfrog” flights of up to 5 miles (8 kilometers), stopping along the way to take samples from compelling areas with diverse geography. It will finally reach the Selk impact crater, where there is evidence of past liquid water, organics – the complex molecules that contain carbon, combined with hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen – and energy, which together make up the recipe for life. The lander will eventually fly more than 108 miles (175 kilometers) – nearly double the distance traveled to date by all the Mars rovers combined.

The planet Titan has a nitrogen-based atmosphere like Earth. Unlike Earth, Titan has clouds and rain of methane. Other organics are formed in the atmosphere and fall like light snow. The moon’s weather and surface processes have combined complex organics, energy, and water similar to those that may have sparked life on our planet.

Titan is larger than the planet Mercury and is the second largest moon in our solar system. As it orbits Saturn, it is about 886 million miles (1.4 billion kilometers) away from the Sun, about 10 times farther than Earth. Because it is so far from the Sun, its surface temperature is around -290 degrees Fahrenheit (-179 degrees Celsius). Its surface pressure is also 50 percent higher than Earth’s.

NASA’s associate administrator for Science was quoted saying, “Titan is unlike any other place in the solar system, and Dragonfly is like no other mission. It’s remarkable to think of this rotorcraft flying miles and miles across the organic sand dunes of Saturn’s largest moon, exploring the processes that shape this extraordinary environment. Dragonfly will visit a world filled with a wide variety of organic compounds, which are the building blocks of life and could teach us about the origin of life itself” he said.

In tens of minutes, Dragonfly will cover several miles or kilometers, farther than any planetary rover has traveled in one day. With one hop per full Titan day (16 Earth days), the rotorcraft will travel from its initial landing site to cover areas several hundred kilometers away during the planned 3.3-year mission. They point out that despite its unique ability to fly, Dragonfly will spend most of its time on Titan’s surface making science measurements.

As partially mentioned before, Dragonfly is nuclear-powered. The current RTG model is the Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator. It is based on the type of RTG flown previously on the two Viking landers and the Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecraft. It’s designed to be used in either the vacuum of space or within the atmosphere of a planet. The excess heat energy from an MMRTG can also be used as a convenient and steady source of warmth to maintain proper operating temperatures for a spacecraft and its instruments in cold environments.

Dragonfly will communicate directly with operators on Earth through NASA’s Deep Space Network, enabled by a large-gain antenna, a medium-gain antenna, a 100-watt traveling-wave tube amplifier and Johns Hopkins APL-designed Frontier radio. At Titan, Dragonfly will rely on a mobility system that includes lidar (light-detection and ranging), inertial measurement units, navigation cameras, pressure sensors and wind sensors.

The actual Moon itself is also very interesting. Cassini showed us that Titan’s surface has rivers, lakes, and even seas of liquid methane (the main component of natural gas), as well as vast expanses of sand dunes. Titan’s atmosphere is composed primarily of nitrogen (about 95%), with some methane (about 5%) and small amounts of other carbon-rich compounds. When exposed to sunlight, the methane and nitrogen molecules are split apart by ultraviolet light and recombine to form a variety of complex organic compounds. Organic molecules are the building blocks for life, and their presence on Titan adds to its intrigue. A mission that SpaceX and the Falcon Heavy will be initially responsible for.

Conclusion

NASA just picked SpaceX and the Falcon Heavy to launch its nuclear-powered drone Dragonfly to Saturn’s Moon Titan. The launch isn’t scheduled to happen until 2028 and will take another 6 years or so to arrive on the Moon. If successful, we’ll have a drone flying around hundreds of millions of miles away, investigating the surface.