NASA Launch Pad Changes In Prep For Artemis II

The first launch of SLS during the Artemis 1 mission was successful in practically every aspect. However, not long after the launch NASA reported some damage to the mobile launch platform and general launch site that wasn’t quite expected. This included excess material spread around the area and primarily damage to the elevators within the launch platform which were destroyed due to the launch.

Now teams are almost complete with both repairs and upgrades to try and prevent any future damage. It seems like there is somewhat of a theme of new rockets and launchpad damage with Starship also coming to mind. While not nearly as bad, SLS had a lot more flame diversion and noise suppression in place yet it still wasn’t enough.

When launching rockets that produce nearly 9 million pounds of thrust at liftoff, the pad infrastructure becomes a complex project and in some cases new territory. Here I will go more in-depth into the upgrades NASA is making, the initial damage to the pad, what to expect in the next few weeks, and more.

Pad Damage

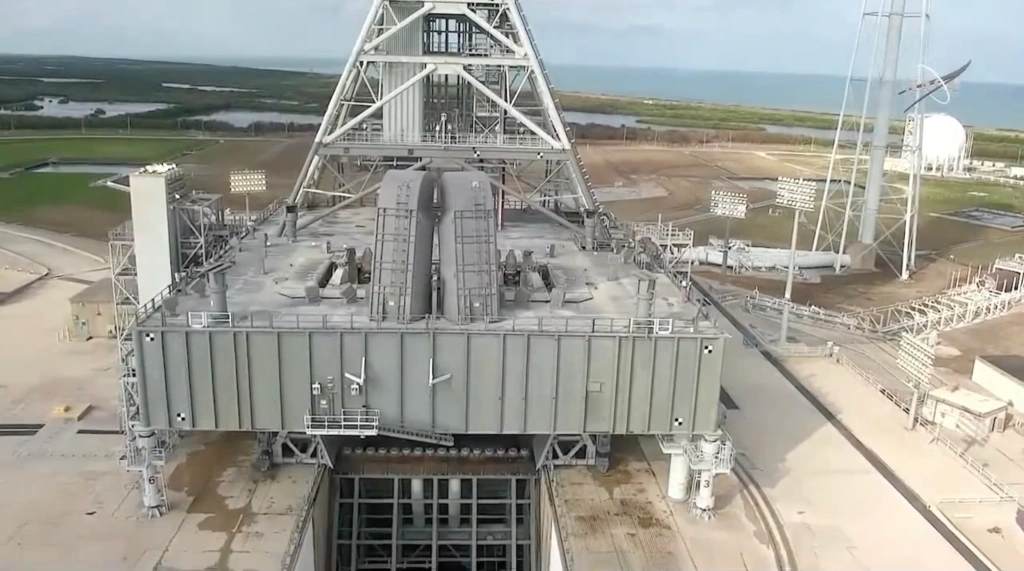

Initially, following the successful liftoff of the Space Launch System from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, teams carefully assessed the mobile launcher and infrastructure at Launch Pad 39B. The agency reported that the ground systems, umbilical retracts on the mobile launcher, software, and ignition over pressure and sound suppression system from the water deluge system, which sprays water to dampen the acoustic shock and protect the deck of the mobile launcher from the flames of the engines, all supported the launch as expected throughout countdown and as the Space Launch System rocket imparted 8.8 million pounds of thrust onto the structure while leaving Earth.

In a quote, Artemis mission manager, Mike Sarafin said, “The exploration ground systems exceeded our expectation for its overall performance. We did have a little bit of damage on the mobile launcher, but it will be ready to support Artemis II and we had accounted for that previously in our pre-plan and our budget for the time between Artemis I and II.”

During the assessment, engineers identified minor damage to umbilicals and the crew access arm on the mobile launcher. Damage to the pneumatic lines associated with gaseous nitrogen and gaseous helium caused the oxygen sensors on the pad to show there were low oxygen readings due to leaks, which teams have since isolated. The most significant issue was the damage to the elevators, which required the team to use the stairs for inspections on the 355-foot-tall tower structure, which has 662 steps, and extended the time required for the inspection. At the time they commented that “The elevators would remain out of service for several months to complete repairs.”

Only four days ago however, the agency released an updated report on the progress of the pad. By now, technicians repaired the elevators on the mobile launcher, and teams are evaluating ways to harden the elevators and strengthen blast doors ahead of Artemis II. Teams are finishing refurbishing the platform’s blast plates surrounding the mobile launcher’s flame hole to protect it against the powerful exhaust plume from the rocket’s engines. At the pad, personnel are modifying the panels on the flame deflector to account for turbulent exhaust flows observed after the first SLS (Space Launch System) launch.

This was an interesting comment from the agency as it highlights that even with so many different systems in place including a flame trench, deflector, water deluge, etc, changes and upgrades were still necessary which take time. In SpaceX’s case, the company launched with only a special type of concrete and an even more powerful rocket than SLS, obviously, we know that the launchpad damage was extensive in that case. As launch vehicles get more powerful and the missions more ambitious, a lot of work and time will likely revolve around the launch pad and not only making sure it survives one launch but withstands it to the point where it can be ready for another soon after.

Focusing back on the SLS pad repairs and upgrades, teams also are testing the crew access arm, the entry and exit point on the mobile launcher astronauts use for access to the Orion spacecraft. This summer, workers will conduct swing tests of the arm to ensure it and supporting mobile launcher systems are certified to support crewed missions. Unlike the first launch, this one will feature a crew of 4 and some changes to general launch operations.

Crew Upgrades

Besides the flame deflector and elevator repairs, work was also being done on a crucial launch safety feature. Specifically, the addition of the emergency egress life safety system. The system provides astronauts and close out crews the ability to safely exit the mobile launcher or Orion in the unlikely event of an emergency during launch countdown. If astronauts and pad personnel need to evacuate, they will proceed to the emergency egress baskets, which are suspended from a catenary system, and travel down to emergency transportation vehicles located at the base of the launch pad. The baskets, which are similar to gondola cars at ski lifts, will be installed on the mobile launcher and tested later this year.

“The emergency egress system is a critical piece supporting the safety of the crew and is dependent on our team being diligent in their work and conducting safe practices,” said Shawn Quinn, Exploration Ground Systems Program manager. “NASA has five core values: safety, integrity, teamwork, excellence, and inclusion. It is no coincidence that safety comes first – the integrity of our work and delivering an emergency egress system are all dependent on our safety values” he said.

The agency said in a statement that “Teams also have nearly completed the emergency egress system terminus area at pad 39B, where the baskets carrying the astronauts or other personnel will arrive following their safe exit from the mobile launcher in an emergency. Emergency transportation vehicles will be stationed there to take the astronauts and remaining personnel safely away from the launch pad. The terminus area will be completed by the end of this month in preparation for mobile launcher arrival at the pad later this summer for tests.”

Other upgrades to pad 39B include completing construction of the additional 1.4-million-gallon liquid hydrogen sphere used for propellant loading. Having two liquid hydrogen spheres at the pad allows teams to minimize time between launch attempts for resupplying liquid hydrogen. Once construction is complete in July, workers will test the new tank by flowing liquid hydrogen to and from it while the mobile launcher is at the pad. In July, teams also expect to complete the environmental control system at the pad, which provides air supply, thermal control, and pressurization to SLS and Orion. Engineers will demonstrate the system as part of the verification and validation testing.

After the mobile launcher arrives at the launch pad, ground systems teams at Kennedy and the Artemis II crew will conduct a day of launch dry run, including operations for the crew, closeout crew, and the pad rescue team. The test will include being inside crew quarters, putting on their orange Orion Crew Survival System spacesuits, and heading to the launch pad in the new all-electric crew transportation vehicles. Future tests with the crew include demonstrating the end-to-end emergency egress process from the white room – the room inside the mobile launcher’s crew access arm – to the pad evacuation site.

The upcoming mission will launch a crew of four astronauts from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on a Block 1 configuration of the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket. The flight profile is called a hybrid free return trajectory. Orion will perform multiple maneuvers to raise its orbit around Earth and eventually place the crew on a lunar free return trajectory in which Earth’s gravity will naturally pull Orion back home after flying by the Moon.

The initial launch will be similar to Artemis I as SLS lofts Orion into space, and then jettisons the boosters, service module panels, and launch abort system, before the core stage engines shut down and the core stage separates from the upper stage and the spacecraft. With crew aboard this mission, Orion and the upper stage, called the interim cryogenic propulsion stage (ICPS), will then orbit Earth twice to ensure Orion’s systems are working as expected while still close to home. The spacecraft will first reach an initial orbit, flying in the shape of an ellipse, at an altitude of about 115 by 1,800 miles. The orbit will last a little over 90 minutes and will include the first firing of the ICPS to maintain Orion’s path. After the first orbit, the ICPS will raise Orion to a high-Earth orbit. This maneuver will enable the spacecraft to build up enough speed for the eventual push toward the Moon. From here the crew will travel to the Moon before heading back for reentry. If successful, the next step will be Artemis III and actually landing on the surface.

Conclusion

NASA has been busy repairing damage to Launch Pad 39B after the launch of SLS apart of Artmies I. Even though the pad was prepared it still sustained some damage primarily to the elevators. The agency is trying to avoid this in the future with more blast doors and protection in place. We will have to wait and see how it progresses and the impact it has on the space industry.