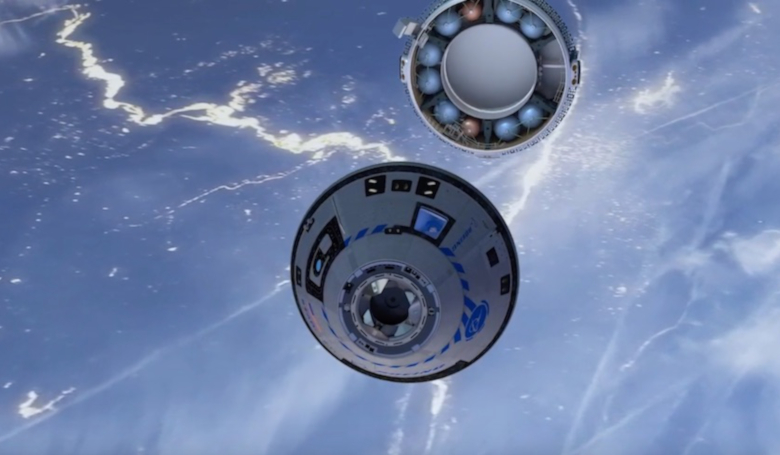

Boeing’s first crewed Starliner launched earlier this month on the 5th and arrived at the International Space Station on the 6th. What was originally intended to be an approximately week-long stay has since been extended by quite a bit. The agency just announced that the new target return date will be June 22nd, about another week away.

The reason has to do with the margin being available, and teams wanting to complete additional testing on the spacecraft along with ensuring they pick a good return date. Here I will go more in-depth into the recent extension, the remaining plans while at the station, what tests need to be completed, and more.

More Testing

When Starliner first launched on the 5th, a specific return date wasn’t set. Instead, the agency commented that the mission was expected to last about one week. In other words, going into it, once Starliner had docked to the station, they had options in terms of how long they could stay, when they would depart, and even the exact landing location after reentry. With this in mind, the first real date we were provided came on June 9th when NASA tweeted saying, “NASA and Boeing Space teams set a return date of no earlier than Tuesday, June 18, for the agency’s Boeing Crew Flight Test. The additional time in orbit will allow the crew to perform a spacewalk on Thursday, June 13, while engineers complete Starliner systems checkouts.”

This leads up to yesterday the 14th when we got another update from the agency. Here in a statement, they commented, “NASA and Boeing now are targeting no earlier than Saturday, June 22, to return the agency’s Boeing Crew Flight Test mission from the International Space Station. The extra time allows the team to finalize departure planning and operations while the spacecraft remains cleared for crew emergency return scenarios within the flight rules” they said.

Providing more of an explanation, Steve Stich, manager of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program was quoted saying, “We are continuing to understand the capabilities of Starliner to prepare for the long-term goal of having it perform a six-month docked mission at the space station. The crew will perform additional hatch operations to better understand its handling, repeat some ‘safe haven’ testing and assess piloting using the forward window” he said.

Interestingly, in addition to some of these general checkouts, they also are doing some extra thrusters checks. Specifically, the agency wrote in a statement, “NASA and Boeing teams also prepared plans for Starliner to fire seven of its eight aft-facing thrusters while docked to the station to evaluate thruster performance for the remainder of the mission. Known as a “hot fire test,” the process will see two bursts of the thrusters, totaling about a second, as part of a pathfinder process to evaluate how the spacecraft will perform during future operational missions after being docked to the space station for six months. The crew also will investigate cabin air temperature readings across the cabin to correlate to the life support system temperature measurements” they said.

While this statement doesn’t reference any specific issues, the RCS thrusters have had a few complications so far on this mission. As Starliner began its approach to the space station for docking, five reaction control system thrusters failed off during flight. These are the small thrusters the spacecraft uses for minute adjustments on orbit such as docking to the ISS. When the issue was found they decided to hold the spacecraft and run some tests. Officially they waited at the 200 meter hold point near the station. The tests consisted of hot firing the affected thrusters. This managed to re-enable four of the five thrusters while the crew manually piloted the spacecraft at the station’s 200-meter hold.

Also, one of Starliner’s aft-facing reaction control system (RCS) thrusters, capable of about 85 pounds of thrust, remains de-selected as teams continue to evaluate its performance. Ground teams plan to fire all 28 RCS thrusters after undocking to collect additional data signatures on the service module thrusters before the hardware is expended.

All this being said, the agency and Boeing don’t seem too concerned with a lot of these complications. In regard to the mission extension to the 22nd, Mark Nappi, vice president and program manager of the Commercial Crew Program at Boeing was quoted saying, “We have an incredible opportunity to spend more time at station and perform more tests which provides invaluable data unique to our position. As the integrated NASA and Boeing teams have said each step of the way, we have plenty of margin and time on station to maximize the opportunity for all partners to learn – including our crew” he said.

It seems that both NASA and Boeing would like a bit more time at the station to not only conduct science but also make sure the spacecraft is capable of a safe and controlled departure followed by re-entry. The upcoming tests including the thruster firings should help keep track of the system’s performance and eliminate any thruster complications for the rest of the mission. In a few days on the 18th, they plan to hold a media briefing where we can expect to receive even more information on the extension and what the plan is in the following days.

Time At The Station

The overall goal of this mission is to certify Starliner as a safe and capable crew vehicle for future flights to the station. As a part of this, the crew has been very busy over the last week or so. So far, NASA astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams have completed numerous flight objectives required for NASA certification of Boeing’s transportation system for flights to the orbiting laboratory under the agency’s Commercial Crew Program. Over the past three days in particular, Wilmore and Williams have performed tasks as part of the space station team, including installing research equipment, maintaining the lab’s hardware, and helping station crewmembers Matt Dominick and Tracy Dyson prepare for a spacewalk.

Starting on the 7th about 1 day after docking, they first unloaded cargo, charged tablets and reviewed emergency procedures to prepare for the “safe haven” operational capability checkout. Wilmore and Williams also met with Boeing teammates on the ground to talk about their experiences so far, including crew-interactive type items like spacesuits, seats, cargo bag placement, maneuverability in the interior, food, sleeping arrangements, hatch operations and lighting.

The next day began with Boeing engineers and flight control teams powering the spacecraft down and back up ahead of a scheduled “safe haven” demonstration. The ability to shelter in the spacecraft or depart the station quickly is a requirement of any visiting crew vehicle. In the “safe haven” configuration, Starliner’s own systems would be used to provide air and other essentials to astronauts during a contingency. Expedition crews occasionally move into their spacecraft if space debris is predicted to pass by or if solar radiation is higher than usual. “We practiced a safe haven event where we would use this as a lifeboat. If something, say a conjunction or something was about to intercede with the space station, some space debris, then we would all go scurry to our spacecraft and hunker down and hopefully everything passes. We went through that process today, closing the hatches, everything, and it was quite a successful event,” said Wilmore.

On the 9th, Wilmore and Williams performed docked space-to-space audio checks, installed a window cover designed for long-duration missions, and performed a dry run of undock vehicle power up and propulsion system checkout procedures. Starliner’s Service Module batteries were also checked out and are fully charged for the next leg of the Crew Flight Test journey.

By the 11th, the crew continued supporting International Space Station activities, having worked through all Starliner flight test objectives and operational capability checkouts with the exception of those associated with the next phase of flight. “Our experienced test pilots have been overwhelmingly positive of their flight on Starliner, and we can’t wait to learn more from them and the flight data to continue improving the vehicle,” said Mark Nappi, vice president and program manager, Boeing’s Commercial Crew Program. Wilmore and Williams also spent Tuesday working on biomedical activities and gene sequence training.

Most recently, on June 13, they helped astronauts Matt Dominick and Tracy Dyson suit-up and prepare for a planned spacewalk to remove a faulty electronics box from a communications antenna on station and to collect samples of microorganisms on the exterior of the orbiting laboratory. When the spacewalk was later called off, Wilmore and Williams helped Dominick and Dyson get back out of their extravehicular activity spacesuits. Later, the Starliner crew took an inventory of the food, and water that have been used up to this point. They also worked with flight controllers to update a USB drive that is often refreshed with new information for return scenarios, like weather conditions, that can be downloaded to their tablets and used for an unlikely situation where crew would need to quickly leave the ISS.

Eventually on the 22nd, assuming the date doesn’t change, Starliner will be packed, powered up, and prepared for departure. Then, the docking mechanism disengages, letting Starliner slowly drift away from the space station. After a flyaround inspection, Starliner conducts a series of burns to take it safely away and position it for deorbit. This leads into Earth reentry and finally a landing.

Conclusion

It looks like Starliner will be staying a bit longer at the Space Station than originally planned. They are now targeting a date of June 22nd which gives them more time to conduct tests and certify the spacecraft for future crewed missions. We will have to wait and see how it progresses and the impact it has on the space industry.