NASA Can’t Afford To Keep Developing The SLS Rocket

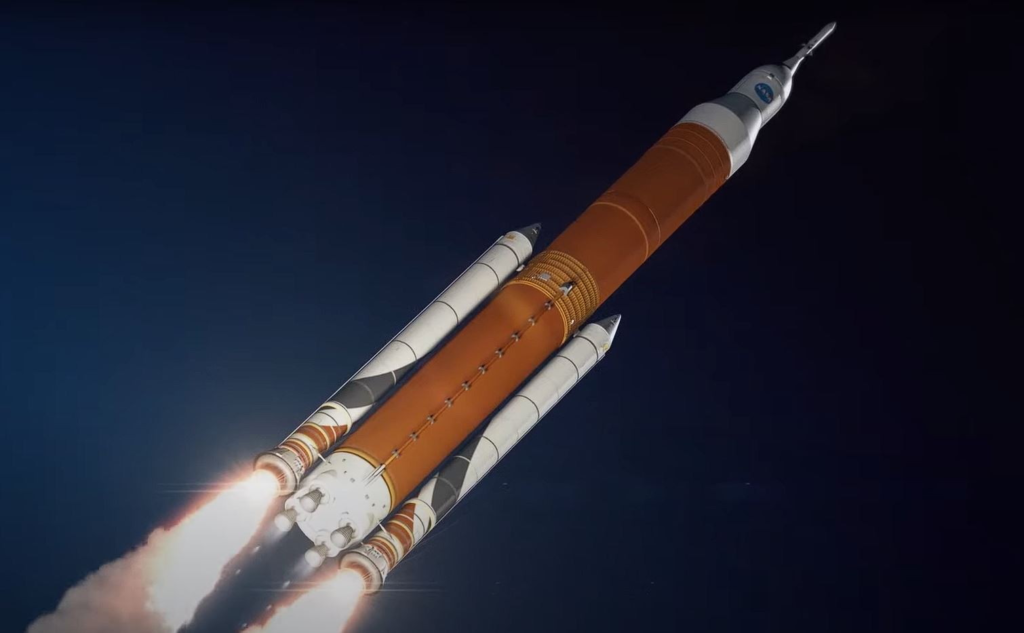

NASA requested $11.2 billion in the fiscal year 2024 president’s budget request to fund the SLS program through fiscal year 2028. This comes in addition to the $11.8 billion already spent developing the initial capability. All of this money is just for the Space Launch System rocket, the main launch vehicle for current and future Artemis missions.

A recent audit however has found that these high prices are unaffordable even for the agency, and could have significant impacts down the line. NASA is currently in the process of manufacturing and testing SLS hardware for not only Artemis II, but Artemis III and beyond as well. Unfortunately, the audit found that each new core stage for example is costing the agency more than the previous.

With NASA only just starting to return to the Moon after the recent success of Artemis I, they need to figure out a solution and fast. If the Space Launch System can’t continue to launch within the agency’s budget, they will need a system that can. Here I will go more in-depth into what the audit found, the true cost of SLS, its current production, and more.

“Unaffordable”

The recent audit was completed by the GAO or the United States Government Accountability Office. This 21-page report highlighted the future plan of SLS in relation to the Artemis missions and why NASA needs to improve its transparency among other things. The report was quoted saying, “The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) does not plan to measure production costs to monitor the affordability of its most powerful rocket, the Space Launch System (SLS).”

They continued to point out that after SLS’s first launch late last year, NASA plans to spend billions of dollars to continue producing multiple SLS components, including core stages and rocket engines, needed for future Artemis missions. The program is also working to produce hardware for more capable versions of the SLS, such as the Block 1B and Block 2, for use on later missions.

The report went on to highlight that not only is this development and manufacturing costing too much, but the agency is failing to keep track of the exact costs. They are quoted saying, “Because the original SLS version’s cost and schedule commitments, or baselines, were tied to the launch of Artemis I, ongoing production and other costs needed to sustain the program going forward are not monitored. These ongoing production costs to support the SLS program for Artemis missions are not captured in a cost baseline, which limits transparency and efforts to monitor the program’s long-term affordability” they said.

Funny enough, nearly a decade ago in 2014, the GAO recommended that NASA develop a cost baseline that captures production costs for the missions beyond Artemis I that fly SLS Block I. NASA intends to fly SLS Block I for Artemis II, planned for 2024, and Artemis III, planned for 2025. The GAO is confident that a cost baseline would increase the transparency of ongoing costs associated with SLS production and provide necessary insights to monitor program affordability. NASA partially concurred, but has not yet implemented this recommendation.

The audit went on to say, “Senior NASA officials told GAO that at current cost levels, the SLS program is

unaffordable.” While there are quite a few more projects within the Artemis program that don’t just include SLS, this rocket takes up a good portion of the money which is why it’s so important. For example, the SLS program accounts for more than one third of NASA’s budget request for programs required to return to the moon. In the president’s budget submission for fiscal year 2024, NASA requested $6.8 billion for the five programs that will be required for Artemis III. The SLS program accounted for about $2.5 billion, or 37 percent of that request.

The report finished by saying, “As of July 2023, the program has not updated its 5-year production and operations cost estimate to reflect the current expected costs for the SLS program. Without regular updates, cost estimates lose their usefulness as predictors of likely outcomes and as benchmarks for meaningfully tracking progress. As a result, it is unclear what the current estimates are to produce SLS hardware covered by the fiscal year 2024 budget request” they said. A problem that needs to be solved soon if NASA truly wants to return humans to the Moon, and for good.

More High Costs

Unfortunately, for the agency, this was just one of multiple recent audits that revealed problems with the SLS program and specifically high prices. Earlier this year, the NASA Office of Inspector General released a full 56-page report on both SLS booster and engine contracts. The report not only highlighted that there could be delays in the future, but the amount of money spent was extremely high.

All the way back around 2015 NASA awarded Aerojet Rocketdyne a combined total of $5.7 billion apart of a Restart and Production program, meant to upgrade and produce a certain amount of engines. To be specific, NASA initially awarded the company $2.1 billion under a program named “Adaptation” between June 2006 to September 2020, and $3.6 billion for the Restart and Production program, from November 2015 to September 2029. This was for the RS-25 engine which SLS uses four of on the first stage for a majority of its thrust. In May, a full report titled “NASA’s Management of The Space Launch System Booster and Engine Contracts” was released. This report was completed by the Office of Inspector General which commonly comes out with information and is critical of the agency as necessary.

In the new audit, they examined the extent to which NASA is meeting cost, schedule, and performance goals for the Boosters and Adaptation contracts, and whether the RS-25 Restart and Production, the follow-on production contracts, reduce the government’s financial risk and promote affordability. In short, they don’t. In the very first sentence, they say “NASA continues to experience significant scope growth, cost increases, and schedule delays on its booster and RS-25 engine contracts, resulting in approximately $6 billion in cost increases and over 6 years in schedule delays above NASA’s original projections.

These increases are caused by long-standing, interrelated issues such as assumptions that the use of heritage technologies from the Space Shuttle and Constellation Programs were expected to result in significant cost and schedule savings compared to developing new systems for the SLS. However, the complexity of developing, updating, and integrating new systems along with heritage components proved to be much greater than anticipated, resulting in the completion of only 5 of 16 engines under the Adaptation contract. They continued by saying, “While NASA requirements and best practices emphasize that technology development and design work should be completed before the start of production activities, the Agency is concurrently developing and producing both its engines and boosters, increasing the risk of additional cost and schedule increases.”

To add to all of this they said “Additionally, Marshall Space Flight Center procurement officials who oversee all four contracts are challenged by inadequate staff, their lack of experience, and limited opportunities to review contract documentation. Specifically, inadequate procurement management led us to question $24.5 million in payments to Northrop Grumman to resolve a disputed request for equitable adjustment (REA) of award fee payments.

Further, NASA used cost-plus contracts at times where we believe fixed-price contracts should have been considered to potentially reduce costs, including the addition of 18 new production engines under the RS-25 Restart and Production contract. In addition, contractors did not receive accurate performance ratings in accordance with federal requirements, such as the “very good” rating awarded to Aerojet Rocketdyne on the end-item Adaptation contract despite only finishing 5 of 16 engines. As a result, we question $19.8 million in award fees it received for the 11 unfinished engines which were subsequently moved to the RS-25 Restart and Production contract and may now be eligible to receive additional award fees.”

A lot of what this report highlights is that NASA is paying different contracts an immense amount of money and barely getting anything in return when compared to the original contract. For one last point they commented, “Faced with continuing cost and schedule increases, NASA is undertaking efforts to make the SLS more affordable. Under the RS-25 Restart and Production contract, NASA and Aerojet Rocketdyne are projecting manufacturing cost savings of 30 percent per engine starting with production of the seventh of 24 new engines. However, those savings do not capture overhead and other costs, which we currently estimate at $2.3 billion. Moreover, NASA currently cannot track per-engine costs to assess whether they are meeting these projected saving targets” they said. These different problems combined are a real threat to the Artemis program and the agency’s future plans surrounding the Moon. Without action, these different costs will eventually be too high and completely halt progress.

Conclusion

NASA is in the process of manufacturing Artemis components for the next few missions. Recent audits suggest that the agency has a transparency issue and simply can’t afford to keep up SLS production at the current rate. This comes in addition to high prices on the rocket’s primary components such as the engines. We will have to wait and see how it progresses and the impact it has on the space industry.