Is The Boeing Starliner Ready To Carry Humans?

For over a decade now, the Boeing Starliner spacecraft has been under development, gone through testing, and performed two uncrewed orbital test flights. All of which in hopes of achieving certification from NASA to begin participating in consistent crewed missions. While the two past launches each had their own respective complications, both Boeing and NASA are confident that the spacecraft is now ready for humans.

After both these past flights and especially the first, the agency and Boeing made significant changes to the spacecraft to ensure what went wrong never happened again. Even though they were very thorough, issues still arose on the second orbital flight. This brings up questions on exactly what was done to prepare Starliner for each mission.

With the first crewed orbital flight test just months away, the safety and reliability of this system are of the utmost importance. Here I will go more in-depth into the changes made to Starliner, the issues NASA and Boeing are working to avoid, what to expect in the near future, and more.

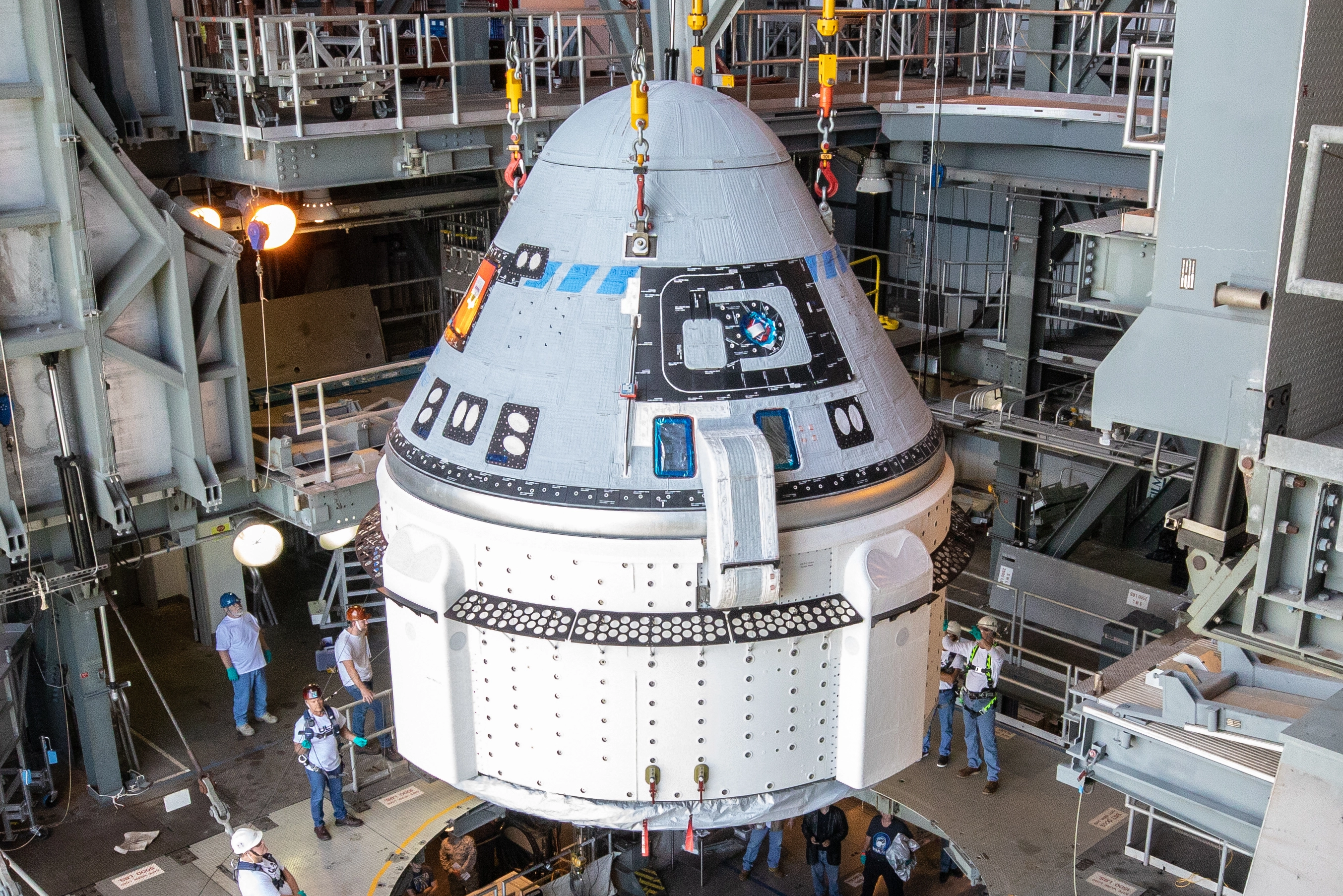

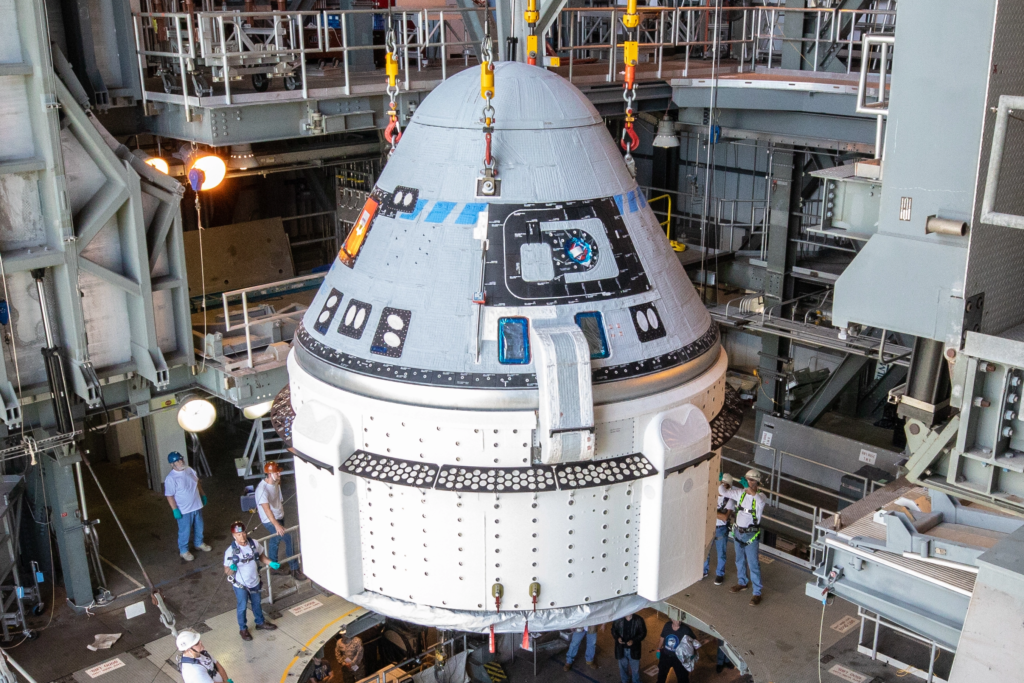

Starliner Changes

The uncrewed orbital flight test launched on December 20, 2019, but after deployment, an 11-hour offset in the mission clock of Starliner caused the spacecraft to compute that “it was in an orbital insertion burn”, when it was not. This caused the attitude control thrusters to consume more fuel than planned, precluding a docking with the International Space Station. To make matters worse, after the mission NASA stated that two software errors detected during the test, one of which prevented a planned docking with the International Space Station, could each have led to the destruction of the spacecraft, had they not been caught and corrected in time. Before re-entry, engineers discovered the second critical software error that affected the thruster firings needed to safely jettison the Starliner’s service module. The service module software error “incorrectly translated” the jettison thruster firing sequence.

Soon after the mission was complete, NASA and Boeing began a significant investigation to figure out exactly what went wrong and ensure it never happened again. By December 2019, they had completed this review. The review team identified 80 recommendations, including 21 suggesting the need for greater hardware and software integration testing; performance of an end-to-end “run for record” test prior to each flight using the maximum amount of flight hardware available; reviewing subsystem behaviors and limitations; and addressing any identified simulation or emulation gaps.

10 recommendations including an assessment of all software requirements with multiple logic conditions to ensure test coverage. 35 recommendations including modifications to change board documentation; bolstering required participants in peer reviews and test data reviews; and increasing the involvement of subject matter experts in safety critical areas. 7 recommendations include updating the software code and associated artifacts to correct the Mission Elapsed Timer Epoch and Service Module disposal anomalies; and making the antenna selection algorithm more robust. And finally, 7 recommendations such as organizational changes to the safety reporting structure; amending the Independent Verification and Validation (IV&V) approach; and the addition of an external Radio Frequency (RF) filter to reject out-of-band interference.

Boeing and NASA have asked the independent review team to remain engaged as a valuable and important partner in the Starliner’s path to crewed flight. Additionally, lessons learned from Starliner’s first uncrewed flight test were shared across the human spaceflight community to strengthen the industry as a whole. “As vital as it is to understand the technical causes that resulted in the flight test not fulfilling all of its planned objectives, it’s equally as important to understand how those causes connect to organizational factors that could be contributors,” said the associate administrator at NASA. “That’s why NASA also decided to perform a high visibility close call review that looked at our combined teams.”

NASA had also completed the high visibility close call investigation to specifically review the organizational factors within NASA and Boeing that could have contributed to the flight test anomalies. The close call investigation team, established in March, was tasked with developing recommendations that could be used to prevent similar close calls from occurring in the future. The close call team built off the technical findings of the joint independent review team related to the software coding errors made during the development of the spacecraft. The team also received additional briefings, held subject matter expert discussions and conducted interviews across the organizations. All of which to try and make sure Starliner’s next mission would be safe and successful.

Future Mission

After this initial test flight and review process, a few years went by as Starliner prepared for its second uncrewed test flight. Despite all of the recommendations and the thorough review, the next launch attempt would still feature quite a few problems. During the August 2021 launch window, some issues were detected with 13 propulsion-system valves in the spacecraft prior to launch. The spacecraft had already been mated to its launch rocket, United Launch Alliance’s (ULA) Atlas V, and taken to the launchpad.

Attempts to fix the problem while on the launchpad failed, and the rocket was returned to the ULA’s VIF (Vertical Integration Facility). Attempts to fix the problem at the VIF also failed, and Boeing decided to return the spacecraft to the factory, thus cancelling the launch at that launch window. The valves had been corroded by intrusion of moisture, which interacted with the propellant, but the source of the moisture was not apparent. By late September 2021, Boeing had not determined the root cause of the problem, and the flight was delayed indefinitely. Through October 2021, NASA and Boeing continued to make progress and were “working toward launch opportunities in the first half of 2022”, In December 2021, Boeing decided to replace the entire service module and anticipated OFT-2 to occur in May 2022.

The OFT-2 mission launched on May 19, 2022. It again carried Rosie the Rocketeer test dummy suited in the blue Boeing inflight spacesuit. Two Orbital Maneuvering and Attitude Control System (OMACS) thrusters failed during the orbital insertion burn, but the spacecraft was able to compensate using the remaining OMACS thrusters with the addition of the Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters. A couple of RCS thrusters used to maneuver Starliner also failed during docking due to low chamber pressure. Some thermal systems used to cool the spacecraft showed extra cold temperatures, requiring engineers to manage it during the docking. On May 22, the capsule docked with the International Space Station. On May 25, the capsule returned from space and landed successfully. During reentry one of the navigation systems dropped communication with the GPS satellites, but Steve Stich, program manager for NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, said this is not unexpected during reentry.

Even though there were still quite a few issues this launch, unlike the first, there were no instances where the spacecraft would be destroyed in flight if teams on the ground had not intervened. Recently the company delayed the first crewed orbital flight test to July. They did this to close out verification items and manage a busy flight schedule to and from the International Space Station (ISS) during the next few months. “We are very proud of the work the team has done,” said Mark Nappi, vice president and Starliner program manager. “We understand the significance of this mission for both us and NASA. We will launch when we are ready and that includes at a time when the International Space Station can accept our vehicle.”

In a recent statement they said, “Meanwhile, the spacecraft’s integrated vehicle testing is going well. The crew module’s interior is in its flight configuration and cargo is loaded with the exception of late-stow items.” Last week, NASA astronauts and CFT Commander Barry “Butch” Wilmore and Pilot Sunita “Suni” Williams, and backup pilot Mike Fincke, finished the second part of the Crew Equipment Interface Testing milestone. They maneuvered around the spacecraft getting hands-on experience with the tools and equipment they will use during the flight test. Wilmore, Williams and Fincke will also conduct several simulations focused on the spacecraft’s backup manual flight mode for added redundancy in the event of an emergency. Fueling the spacecraft and loading updated software flight parameters ensuring alignment with the ISS will be conducted closer to launch.

After several rounds of competitive development contracts within the Commercial Crew Program starting in 2010, NASA selected the Boeing Starliner, along with SpaceX Crew Dragon, for the Commercial Crew Transportation Capability (CCtCap) contract round. The first crewed test flight test was initially planned to occur in 2017. Since then, SpaceX’s Crew Dragon has been certified and secured a significant number of contracts. While Boeing is behind, they are confident that this upcoming mission will be a success and the start of consistent crewed missions with Starliner.

Conclusion

Boeing and NASA have done a lot of work in the past few years working on the Starliner spacecraft. This has involved nearly 100 recommendations covering a host of different aspects in order to make the capsule safe and reliable. We will have to wait and see how it progresses and the impact it has on the space industry.