Is NASA Making Progress On The Lunar Gateway?

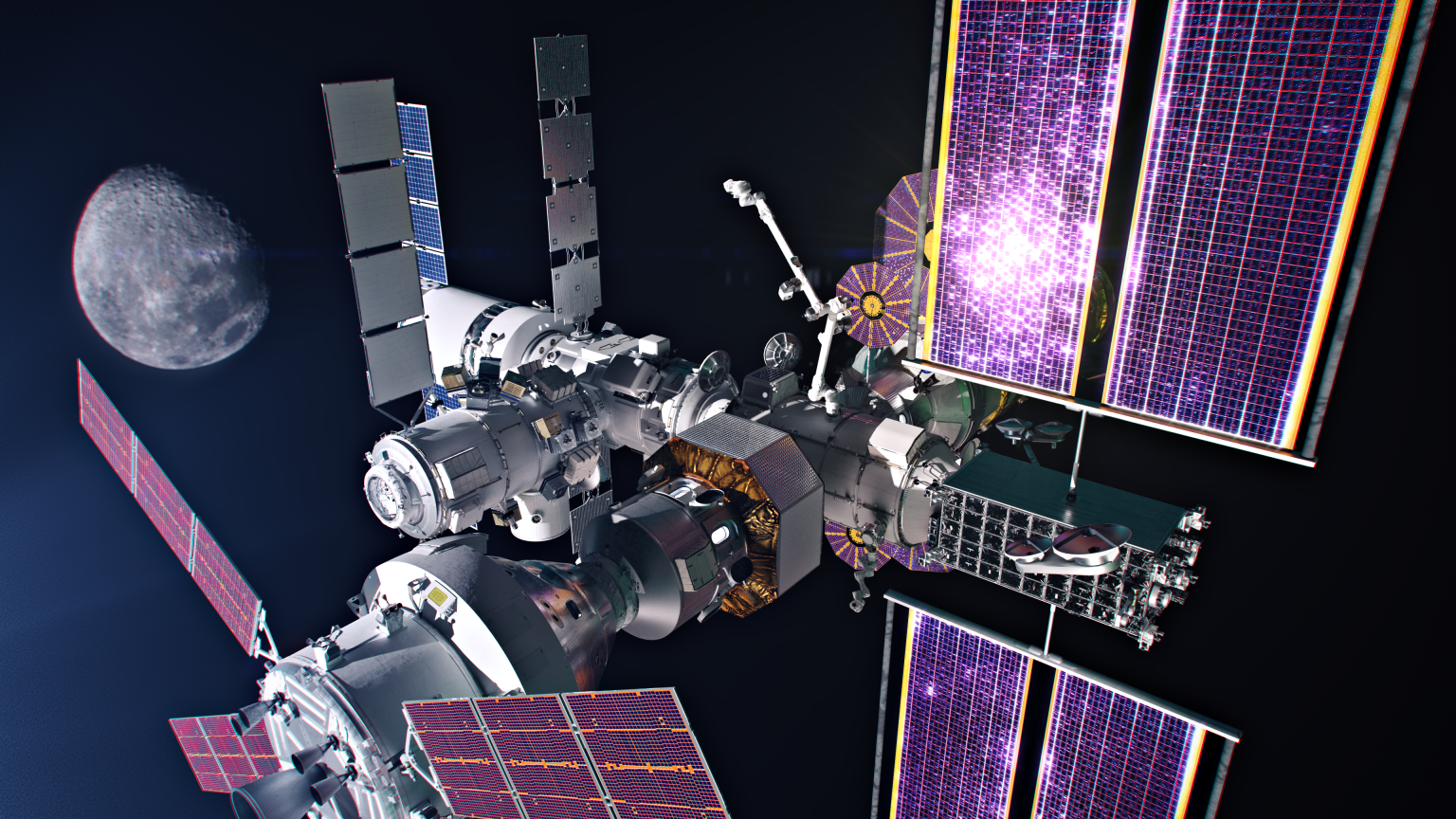

One of the most important pieces in NASA’s return to the Moon is the Gateway lunar space station. Acting as a hub, Gateway is expected to dock with visiting spacecraft, shelter crews before and during their missions, and provide logistics among other benefits. All this being said, new delays and Artemis developments bring up concerns regarding the station’s future.

As of right now, the two initial segments are scheduled to lift off together in October 2025. However, this is expected to change which could shift its development and upcoming milestones. Something NASA needs to ensure stays on track for a timely launch. Here I will go more in-depth into Gateway’s development, questions regarding its launch date, the station’s design, and more.

Launch Date Changes

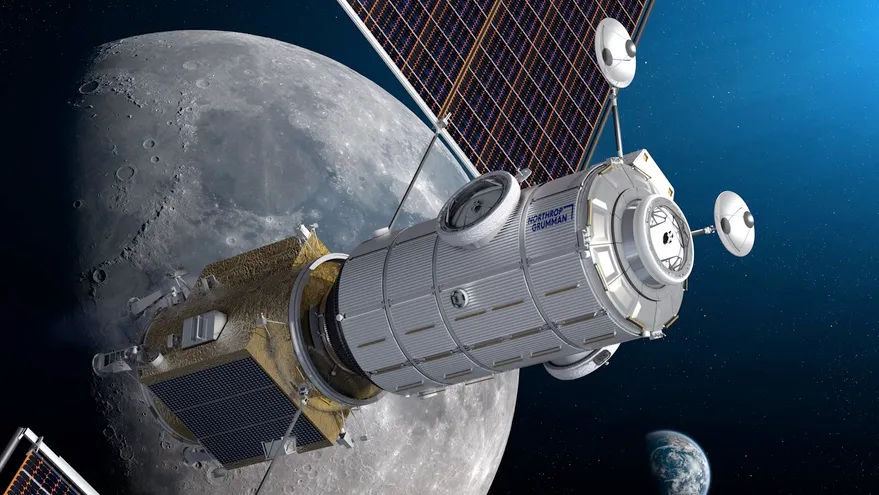

For over a year now, we have received the occasional update on Gateway and its two initial modules. While the station is expected to grow significantly over the next decade, it will start with just two segments. HALO or Habitation and Logistics Outpost, is provided by Northrop Grumman, while the Power and Propulsion Element (PPE) is being built by Maxar Technologies. Both companies were contracted by NASA to develop and create these modules.

In terms of launch date, 3 years ago NASA selected SpaceX to launch both modules together on Falcon Heavy. At the time of that announcement, they were targeting a launch no earlier than May 2024. Eventually, this was changed to October 2025. Both dates aligned with NASA’s goal to have the station ready by Artemis IV, which is the first mission that plans to actually dock to and utilize the station. Unfortunately, just last month the agency announced that Artemis 2 and 3 would be pushed back significantly. In a statement, the agency said, “NASA will now target September 2025 for Artemis II, the first crewed Artemis mission around the Moon, and September 2026 for Artemis III, which is planned to land the first astronauts near the lunar South Pole. Artemis IV, the first mission to the Gateway lunar space station, remains on track for 2028.”

This delayed both Artemis 2 and 3 by at least a year. As for Gateway, even though Artemis IV is still the same, comments from the agency suggest the October launch date could change. In another quote the agency says, “Gateway is making significant progress toward launch of the initial components to lunar orbit. NASA is reviewing the schedule for launch, previously planned for October 2025, to provide additional development time and better align that launch with the Artemis IV mission in 2028.” In other words, the agency is likely going to push its launch date back even further so there isn’t such a large gap between its arrival and its first mission. This could mean a launch in 2025 or 2026 is more realistic.

Either way, progress is still being made on both segments. Late last year NASA revealed that “Fabrication and assembly of Gateway’s Power and Propulsion Element (PPE) are well underway at@Maxar Palo Alto.” At the time they mentioned that “The team recently completed assembly of the PPE’s central cylinder and will place it through a series of tests to ensure the hardware’s integrity for future flight.”

In addition, early last year, engineers from NASA and Aerojet Rocketdyne began qualification testing on the cutting-edge solar electric propulsion (SEP) thrusters. Specifically, the Advanced Electric Propulsion System (AEPS), built by Aerojet Rocketdyne, provides 12 kilowatts of propulsive power – over two times more powerful than current state-of-the-art in-space electric propulsion systems. The AEPS must undergo qualification testing before being certified to fly on Gateway. This exact system is core to the PPE module and its ability to keep Gateway in the proper position and orbit around the Moon.

As for the HALO module, Northrop Grumman has been making progress but has also run into some roadblocks. For example, last year the company took a $36 million charge on its contract, citing changing mission requirements and broader economic issues. In an earnings call, Kathy Warden, chief executive of Northrop Grumman, said “As it’s turning out on the HALO program, the requirements are not as stable as we or the government anticipated, and we’re working with them to address that change management as we go forward.” Even more recently in the past few weeks, we have seen astronauts starting to train on Mock Gateway modules for their eventual mission. At this point, progress is being made but there are a lot of unknowns for both the companies involved and even NASA.

New Lunar Space Station

From the beginning, whether or not this station is worth it has been a hot topic between NASA officials and many others. The agency believes Gateway will play a key role in helping them and their partners test the technologies and capabilities required for a sustained human presence in deep space, and chart a path to Mars. On the other side, many see the station as a significant investment of both time and money that isn’t necessary for the Artemis missions.

Gateway is intended to support sustained exploration and research in deep space, including docking ports for a variety of visiting spacecraft, space for crew to live, work, and prepare for lunar surface missions, and on-board science investigations to study heliophysics, human health, and life sciences, among other areas. As partially mentioned prior, it will start as just two modules but grow significantly over time.

The first two modules are supposed to work together providing a combination of power and habitation. The Power and Propulsion Element is a high-power, 60-kilowatt solar electric propulsion spacecraft that will provide power, high-rate communications between Gateway and Earth, attitude control, and orbital transfer capabilities for Gateway. HALO is one of two habitation elements where astronauts will live, exercise, prepare meals, rest, prepare for lunar surface missions, and conduct research while visiting Gateway. The pressurized living quarters will provide docking ports for visiting spacecraft like NASA’s Orion spacecraft, lunar landers, and logistics resupply craft, and serve as the backbone for command and control and power distribution across Gateway. The module will perform other core functions, including hosting science investigations via internal and external payload accommodations, and communicating with lunar surface expeditions through the HALO-Lunar Communication System, or HLCS, provided by ESA.

The other modules expected to join the station include I-HAB, a refueling module, crew and science airlock, the Deep Space Logistics module, and Canadarm3. All of which will happen between Artemis IV and VI.

Even though the station will continue to grow, the station’s size could be an issue. Early last year, reports came out about the size and interior space of Gateway. According to an architect involved in the station’s design, the living quarters of NASA’s moon orbiting Gateway station will be so tiny that astronauts will not be able to stand upright inside. He was quoted saying, “In other words, that would be a room 2 by 2 by 2 meters [6.6 by 6.6 by 6.6 feet]. And you are locked in there with three other people. There are other rooms but they are not bigger and there are not many of them.” Due to various mass restrictions along with ensuring two of these modules can fit within the launch vehicle, the size of the station has become quite a bit smaller than originally planned. To add to that, on the two initial modules of HALO and PPE, there won’t be any windows. Something astronauts visiting the station may need to get used to during their stay.

While at the Moon, Gateway will be placed in a strategic lunar orbit intended to facilitate easy access and fuel efficiency. To do this, the agency needed to find a combination of two different orbits. For example, a spacecraft in low lunar orbit follows a circular or elliptical path very close to the lunar surface, completing an orbit every two hours. Transit between Gateway and the lunar surface would be quite simple in a low lunar orbit given their proximity, but because of the Moon’s gravity, more propellant is required to maintain the orbit. With Gateway planning to be in orbit for 15+ years, this wouldn’t be efficient over the long run.

On the other hand, a distant retrograde orbit provides a large, circular, and stable (or more fuel-efficient) orbit that circles the Moon every two weeks. However, what Gateway would gain in a stable orbit, it would lose in easy access to the Moon: the distant orbit would make it harder to get to the lunar surface. Combining the two, you get NRHO, marrying the upsides of low lunar orbit (surface access) with the benefits of distant retrograde orbit (fuel efficiency). Hanging almost like a necklace from the Moon, NRHO is a one-week orbit that is balanced between the Earth’s and Moon’s gravity. This orbit will periodically bring Gateway close enough to the lunar surface to provide simple access to the Moon’s South Pole where astronauts will test capabilities for living on other planetary bodies, including Mars. NRHO can also provide astronauts and their spacecraft with access to other landing sites around the Moon in addition to the South Pole.

NRHO will also allow scientists to take advantage of the deep space environment for a new era of radiation experiments, providing a better understanding of the potential impacts of space weather on people and instruments.

Conclusion

NASA’s Gateway Space Station is still somewhat on track for a launch late next year. Unfortunately, it seems that this date will be pushed back no matter the progress as Artemis IV isn’t set to happen until 2028. We will have to wait and see how it progresses and the impact it has on the space industry.