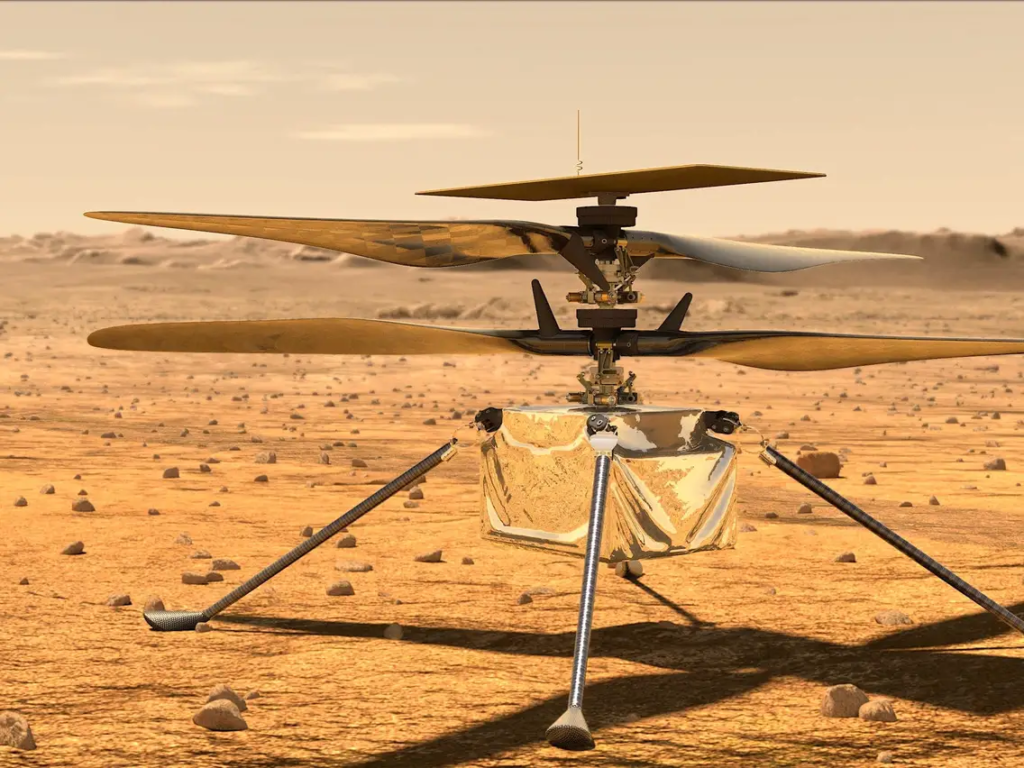

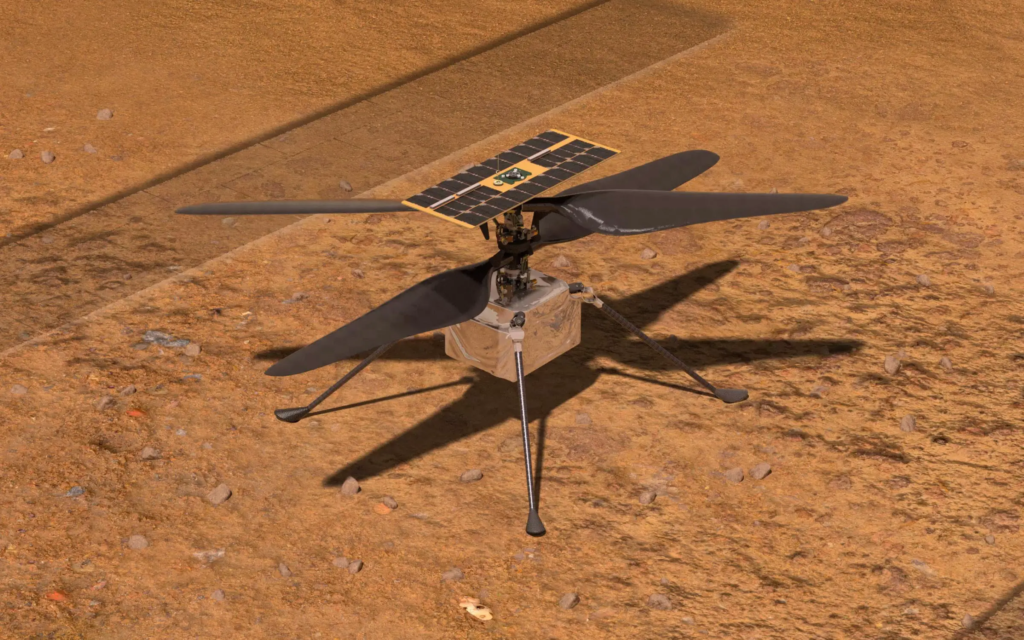

How Is Ingenuity Still Running On Mars?

What was initially intended as a month-long demonstration on the red planet has turned into a multi-year journey. The Ingenuity helicopter on Mars has lasted much longer than the agency anticipated and is continuing to demonstrate its value. Despite a few complications between its first flight and now, the helicopter is still alive on the planet and trying its best to push forward.

One of the main reasons Ingenuity has managed to survive so long has to do with constant problem-solving back on Earth and redundant systems throughout the helicopter. In reality, if it weren’t for these two factors, Ingenuity would have stopped working a long time ago. The extra time to fly around has also helped the Perseverance rover which has been close by the entire journey.

This brings up the question however of how much long can Ingenuity last and what is the helicopters current state. Here I will go more in-depth into the longevity of this tech, how it’s still working today, what the next few months hold, and more.

Helicopter Longevity

Ingenuity landed on Mars on February 18th, 2021. It’s now been over two years of flying and completing various tests. Throughout that 2 plus year period, a lot has happened that determined the milestones and challenges Ingenuity has faced. Around one year ago for example, on May 3rd 2022, Ingenuity’s team of engineers and scientists got their first hint of the hardship to come when they opened their comm logs to find radio silence. The small helicopter, sitting on a planet 240 million km (149 million miles) away, had run out of power while trying to keep itself warm during the cold Martian night. It likely happened in the early morning hours of Sol 426 (May 1st , 2022), a date roughly halfway between the Autumnal equinox and Winter Solstice on Mars. In other words, it was mid-November on the Martian surface.

Despite the overnight loss of power, the sun was still strong enough to revive the helicopter in the morning. This required the helicopter to generate enough electrical power to activate heaters, thaw out the frozen battery, and charge it sufficiently before bringing the avionics back to life. This process, performed by the “Lazarus circuit”, allows the helicopter, like Lazarus of old, to return to life after being effectively dead the night before. The overnight brownout, while not fatal, does reset the onboard clock, causing Ingenuity to lose all sense of time and forget to wake up as scheduled. Instead, the computer wakes up and attempts to talk to the rover 2 hours and 15 minutes after the initial power-on. The exact timing of this entire process is based on a complicated combination of fluctuating factors such as battery charge, wind, dust, and temperature. As each morning’s wakeup was different, the team had to use the helicopter base station on the rover to search for Ingenuity’s signal using a search window covering the predicted wakeup time. Only when a communications link was established could Ingenuity’s clock be synchronized to allow a scheduled activity later in the day.

The Martian winter is a one-two punch of lower insolation (amount of solar energy reaching a given area) and greater dust storm activity. Nighttime temperatures plunged to -85 C (-120 F), requiring more and more power to stay warm. With less solar power, came less energy for flights, eventually grounding the helicopter entirely for two consecutive months. As the primary seasonal dust storm abated, the team managed to resume flying with a series of short, low-energy flights, covering limited distances as it struggled to keep up with the rover. Under normal conditions, Perseverance’s four-legged friend can fly further in 3 minutes than the rover can drive in a day. However, the helicopter’s now extremely limited energy budget made it almost impossible for it to fulfill its role as Perseverance’s faithful companion and scout. Indeed, the nuclear-powered rover carried on much as it had before, driving unperturbed while the helicopter limped doggedly behind it.

One month to the day after the Dec. 24 flight attempt, Ingenuity did something it hadn’t done during the previous 260 sols – it slept “warmly” through the entire night. Data leading up to this event had suggested that such a survival was possible, but 8 long months of winter had tempered the team’s optimism. When Ingenuity’s team reviewed the downlinked data, they found that not only had it started living through the night, but had actually begun to bank power in its batteries. Enough to continue operations not long after.

Current State

Ingenuity’s 48th flight produced a bunch of aerial images showing the exact area of interest at a resolution several orders of magnitude better than anything prior. All of these images were downlinked to Earth and provided to rover planners and scientists. However, that downlink was the last time the team would hear from the helicopter for a long time. Eager to continue up the delta, the team tried and failed to uplink the instructions for Flight 50 several times. Sol after sol, the helicopter remained elusive. Each time, the downlinked telemetry from the Helicopter Base Station (HBS) on the rover would come back showing no radio sign of the helicopter.

Since the first post-winter overnight “survival” on Sol 685, the helicopter had unfortunately been drifting in and out of nighttime survival mode (having enough power to avoid overnight brownouts). These overnight brownouts lead to uncertainty in Ingenuity’s wakeup time, which make planning much harder. The new transitional power state made morning wakeup times even more difficult to predict, with large fluctuations as the helicopter’s power state neared its overnight survival threshold. Constraints with rover power and instrument scheduling generally prevented the team from searching the entire wakeup range every morning. Unsurprisingly, the team had spent a substantial number of sols losing, searching for, and then reacquiring the helicopter over the course of a few weeks.

Thus, the team was not overly concerned when communication was lost with the helicopter on Sol 755. Standard practice had been to methodically search subsets of the expected wakeup window over the course of several sols, eventually building up enough coverage to catch the helicopter’s wakeup. In more than 700 sols operating the helicopter on Mars, not once had we ever experienced a total radio blackout. Even in the worst communications environments, the agency had always seen some indication of activity.

Thankfully, on Sol 761, nearly a week after the first missed check-in, the communications team observed a single, lonely radio ACK (radio acknowledgement) at 9:44 LMST (Local Mean Solar Time), exactly the time when they expected to see the helicopter wakeup. Another single ACK at the same time on Sol 762 confirmed that the helicopter was indeed alive, which came as a welcome relief for the team. Ultimately, this first-of-its-kind communications blackout was a result of two factors. First, the topology between the rover and the helicopter was very challenging for the radio used by Ingenuity. In addition to the aforementioned communications shadow, a moderate ridge located just to the southeast of the Flight 49 landing site separated the helicopter from the rover’s operational area. The impact of this ridge would only abate once the rover had gotten uncomfortably close to the helicopter. Second, the HBS antenna is located on the right side of the rover, low enough to the deck to see significant occlusion effects from various part of the rover.

This being said, despite the imminent return of Martian summer, it now appears that the dust covering the solar panel will ensure that Ingenuity will likely remain in this transitional power state for some time. Its important to point out that as the Martian year is twice as long as Earth’s, so too are its seasons. In the past, engineers had to find a way to operate in this new normal. Ingenuity’s heaters normally kept its internal components at a comfortable -15 C, but with a complete power loss every night, components were being subjected to far more extreme temperatures. The first casualty was the inclinometer, which failed soon after the start of winter operations. Dealing with this failure and adapting to the new operations paradigm consumed precious time while the Sun grew darker with each passing sol. The team managed only a single checkout flight before winter came in earnest.

The last Ingenuity flight was two months ago in April. Since then, teams have been working to contact the helicopter and monitor the power situation. At its core, Ingenuity is a technology demonstration to test powered, controlled flight on another world for the first time. It hitched a ride to Mars on the Perseverance rover. Once the rover reached a suitable “airfield” location, it released Ingenuity to the surface so it could perform a series of test flights over a 30-Martian-day experimental window. Between then and now it managed to fly a combined total of over 90 minutes on Mars. Hopefully, in the near future, it continues its journey.

Conclusion

Ingenuity was meant to fly a few times and test various systems for around a month. By now it’s been flying somewhat consistently for more than two years. This impressive feat has been far from easy with many complications along the way. We will have to wait and see how it progresses and the impact it has on the space industry.