Artemis III Might Not Land Humans On The Surface

NASA is heading back to the Moon and is aiming to land humans on the surface during Artemis III, scheduled for late 2025. However, despite this process being completed around half a century ago, it’s by no means easy and involves a lot of moving parts. Even if just one aspect is delayed, it could compromise the entire mission.

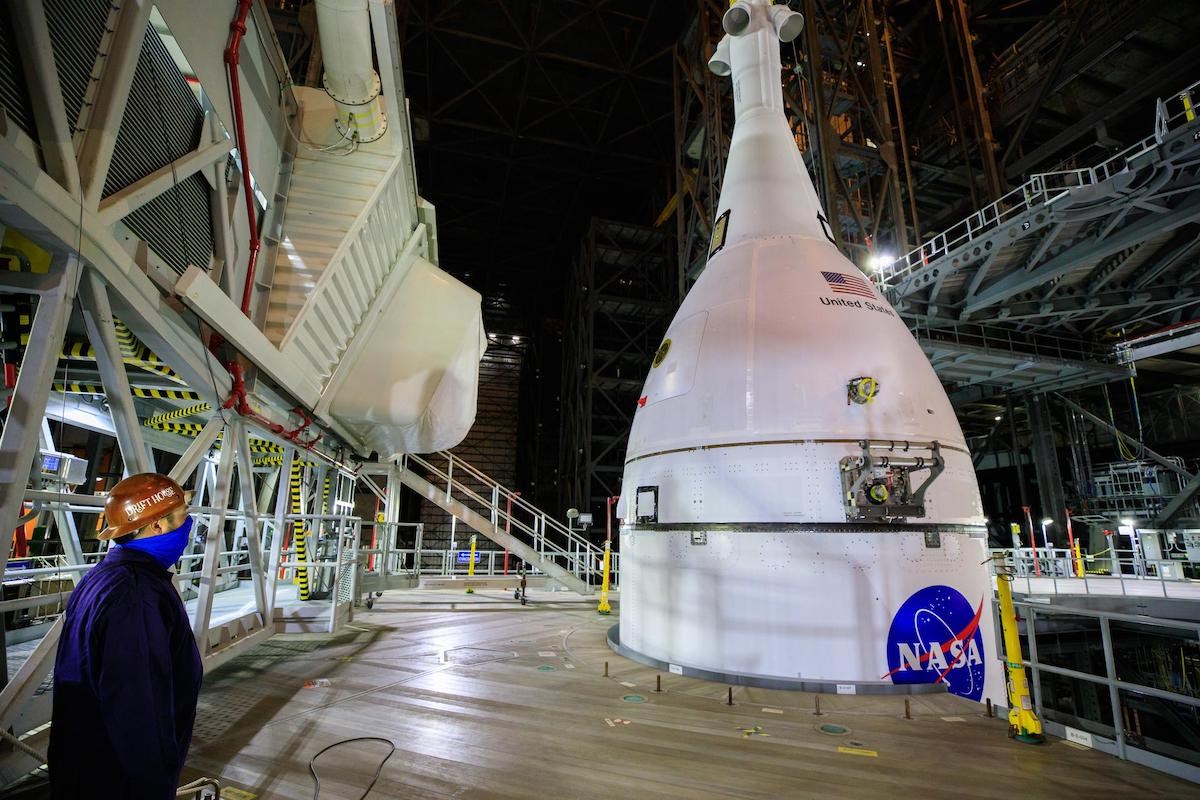

This is the problem NASA is currently running into as the launch date gets closer and closer. Between the Gateway space station, Orion spacecraft, SLS rocket, and the SpaceX Human Landing System, there is a lot of work that still needs to be completed. Recent comments from agency officials even suggest that they may change the flight profile of the mission if certain projects aren’t ready.

This could turn the long-awaited moon landing attempt into another practice run similar to Artemis II. Something NASA needs to avoid in order to stay somewhat on schedule in relation to future Moon operations. Here I will go more in-depth into the possible Artemis III changes, the mission’s progress, impact of Artemis II, and more.

Mission Concerns

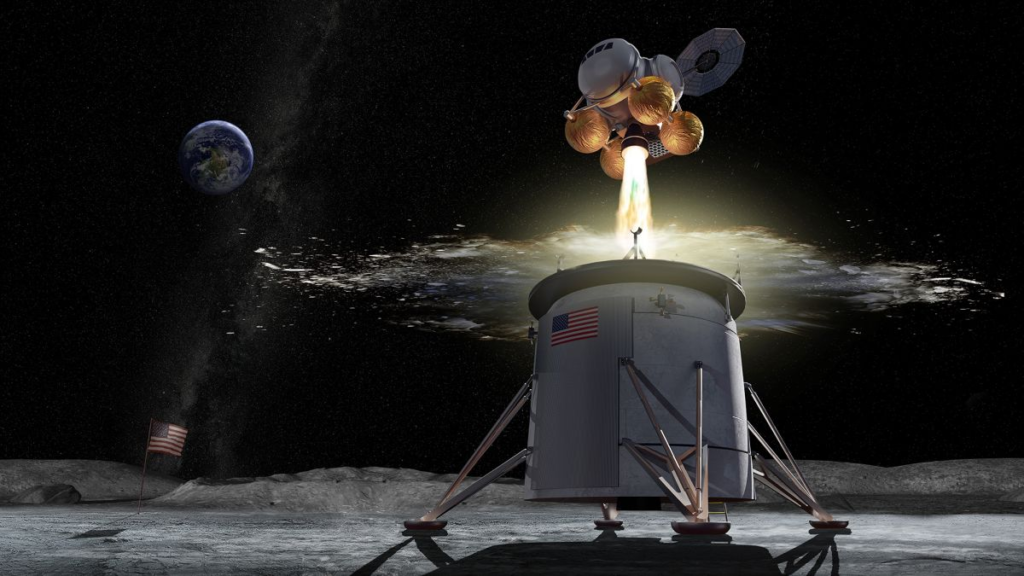

Around two months ago, speaking at a joint meeting of the National Academies’ Aeronautics and Space Engineering Board and Space Studies Board, Jim Free, NASA associate administrator for exploration systems development, said Artemis 3 was in danger of being delayed from December 2025 to some time in 2026. He went on to clarify that SpaceX and the Starship HLS system in particular was what he was worried about. Specifically, he pointed out the number of Starship launches that SpaceX has to carry out to be ready for Artemis 3. Each Starship lander mission requires launching the Starship lander itself as well as several “tanker” Starships to fuel the lander in Earth orbit before it goes to the moon.

“That’s a lot of launches to get those missions done,” Free said. “They have a significant number of launches to go, and that, of course, gives me concern about the December of 2025 date” for Artemis 3. He continued by saying, “With the difficulties that SpaceX has had, I think that’s really concerning. You can think about that slipping probably into ’26” he said.

More recently, speaking at an Aug. 8 briefing at the Kennedy Space Center, he talked about the possibility of changing the Artemis III mission plan depending on what’s ready. “We may end up flying a different mission if that’s the case,” he said. “If we have these big slips out, we’ve looked at if can we do other missions.” Artemis 3 could also change based on the outcome of Artemis 2, he added. “One thing we learned from ISS is to make sure we’re flexible so we keep human spaceflight viable,” he said, such as changing the assembly sequence of the station based on when hardware was available. “I think it’s incumbent upon us to do that,” he said. “We’re trying to look at all of the missions that we could fly to keep learning.”

As far as what could change, instead of landing humans on the surface, they could instead just dock to Gateway. This is assuming however that the Gateway station is also ready by 2025. Another option would be a mission similar to Artemis II where the crew goes through some of the general operations while orbiting the Moon. Neither option is ideal and would end up delaying the main goal which is returning humans to the surface.

While Free made quite a few comments focusing on SpaceX and their contribution, there is also concern about NASA’s contributions. Mainly, the outcome of Artemis II and how that impacts the next mission’s schedule. Even though this launch is still scheduled for next year, the date is approaching very quickly. If something were to happen that pushes this launch back, it would almost certainly push Artemis III back just as much if not more. This is part of the reason NASA is determined to get Artemis II off the ground on time.

Artemis II Update

Over the past few months, we have heard quite a bit relating to the next mission to the Moon. The mission will be to confirm all of the spacecraft’s systems operate as designed with crew aboard in the actual environment of deep space.

Most recently, a critical auxiliary target for NASA’s Artemis II mission was marked as ready for flight following testing at United Launch Alliance’s (ULA) Florida facility. Teams with the company added the target onto the in-space propulsion stage for NASA’s SLS (Space Launch System) rocket at ULA’s Delta Operations Center at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida, May 16. Following the safe separation of NASA’s Orion spacecraft from the rocket’s upper stage, the four astronauts aboard Orion will use the target affixed to the in-space stage for a proximity operations demonstration to test Orion’s piloting qualities. The recently installed target underwent illumination testing in May to ensure the target will be visible in the different lighting conditions of space.

The SLS rocket delivers propulsion in phases to send the Artemis missions to the Moon. Its ICPS (interim cryogenic propulsion stage) and its single RL10 engine fires twice during the Artemis II mission to put the Orion spacecraft and astronauts into a high-Earth orbit, where they will then check out Orion’s manual handling qualities using the ICPS and its auxiliary target before then heading to the Moon.

During the demonstration, astronauts will use the two-foot target to test navigation and other critical Orion systems to assess its ability to approach and fly alongside another large spacecraft in space before future Artemis missions that require docking capabilities.

On the actual mission, NASA will launch a crew of four astronauts from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on a Block 1 configuration of the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket. The flight profile is called a hybrid free return trajectory. Orion will perform multiple maneuvers to raise its orbit around Earth and eventually place the crew on a lunar free return trajectory in which Earth’s gravity will naturally pull Orion back home after flying by the Moon.

The initial launch will be similar to Artemis I as SLS lofts Orion into space, and then jettisons the boosters, service module panels, and launch abort system, before the core stage engines shut down and the core stage separates from the upper stage and the spacecraft. With crew aboard this mission, Orion and the upper stage, called the interim cryogenic propulsion stage (ICPS), will then orbit Earth twice to ensure Orion’s systems are working as expected while still close to home. The spacecraft will first reach an initial orbit, flying in the shape of an ellipse, at an altitude of about 115 by 1,800 miles. The orbit will last a little over 90 minutes and will include the first firing of the ICPS to maintain Orion’s path. After the first orbit, the ICPS will raise Orion to a high-Earth orbit. This maneuver will enable the spacecraft to build up enough speed for the eventual push toward the Moon. The second, larger orbit will take approximately 23.5 hours with Orion flying in an ellipse between about 115 and 46,000 miles above Earth. For perspective, the International Space Station flies a nearly circular Earth orbit about 250 miles above our planet.

After completing checkout procedures, Orion will perform the next propulsion move, called the translunar injection (TLI) burn. With the ICPS having done most of the work to put Orion into a high-Earth orbit, the service module will provide the last push needed to put Orion on a path toward the Moon. The TLI burn will send crew on an outbound trip of about four days and around the backside of the moon where they will ultimately create a figure eight extending over 230,000 miles from Earth before Orion returns home.

During the remainder of the trip, astronauts will continue to evaluate the spacecraft’s systems, including including demonstrating Earth departure and return operations, practicing emergency procedures, and testing the radiation shelter, among other activities. The Artemis II crew will travel 6,400 miles beyond the far side of the Moon. From this vantage point, they will be able to see the Earth and the Moon from Orion’s windows, with the Moon close in the foreground and the Earth nearly a quarter-million miles in the background.

With a return trip of about four days, the mission is expected to last just over 10 days. Instead of requiring propulsion on the return, this fuel-efficient trajectory harnesses the Earth-Moon gravity field, ensuring that—after its trip around the far side of the Moon—Orion will be pulled back naturally by Earth’s gravity for the free return portion of the mission. “The unique Artemis II mission profile will build upon the uncrewed Artemis I flight test by demonstrating a broad range of SLS and Orion capabilities needed on deep space missions,” said Mike Sarafin, Artemis mission manager. “This mission will prove Orion’s critical life support systems are ready to sustain our astronauts on longer duration missions ahead and allow the crew to practice operations essential to the success of Artemis III.”

Over the next few months, we can expect even more updates on this mission as both the crew and NASA prepare to launch. If everything goes according to plan a launch next year is possible, helping keep Artemis III on schedule as well.

Conclusion

NASA is trying to prepare not only for Artemis II but also III. Some officials are concerned about SpaceX’s contribution among others to the point where they are considering alternate mission options. We will have to wait and see how it progresses and the impact it has on the space industry.