A Russian ISS Module Is Leaking Toxic Ammonia

Last year in December, a Russian Soyuz MS-22 crewed spacecraft leaked all of its coolant leaving its astronauts without a ride home for the time being. Only a few months later a different Progress spacecraft reported a depressurization thanks to a leak in the vehicle’s coolant system. Now in October, new reports are coming out that toxic ammonia flakes were observed on the station’s Russian Multipurpose Laboratory Module due to another possible leak.

Specifically, flight controllers noticed the leak and relayed that information to astronauts on board who were able to visibly confirm it. With this information only just coming out, NASA and Roscosmos are still trying to figure out the best course of action and decide the next steps. While not ideal, they both made it clear that astronauts on board are not in any danger.

This leak marks the third instance within a year for Russian hardware visiting or apart of the station to have difficulties. It also adds to the conversation of NASA’s plans with the station and its eventual retirement and de-orbit. Here I will go more in-depth into the new leak, plans to fix it, what it means for the future of the station, and more.

Visible Flakes

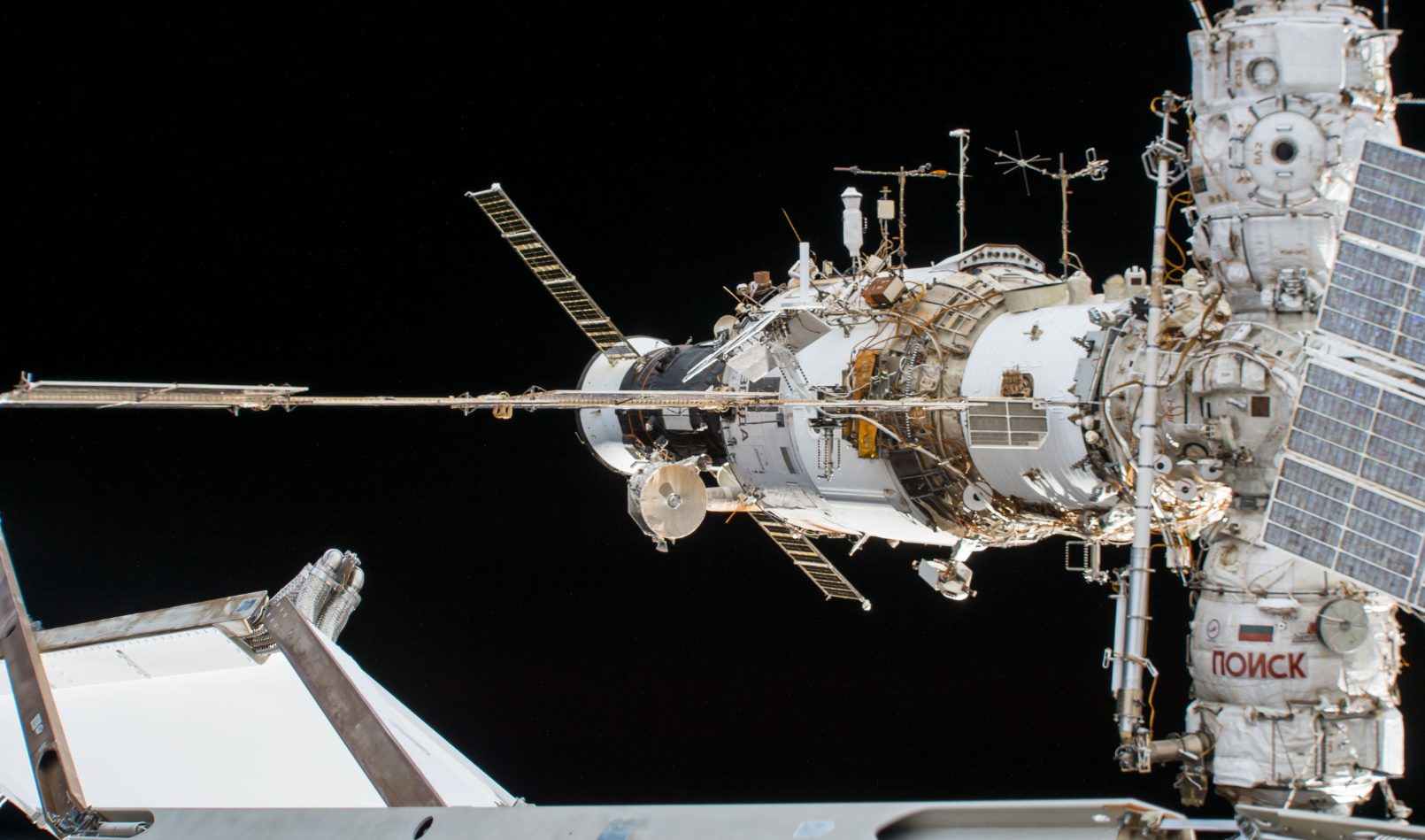

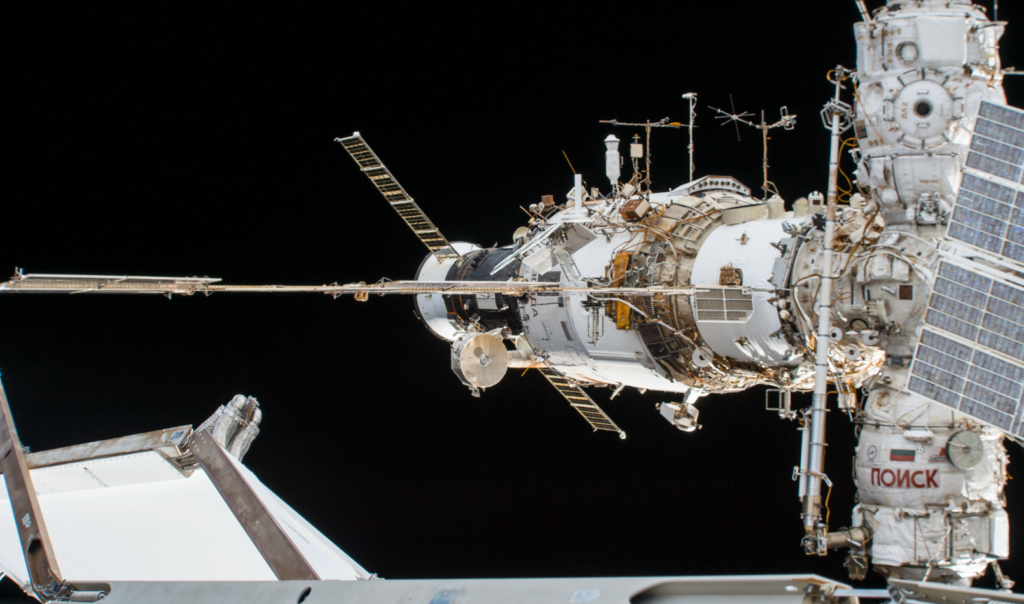

At approximately 1 p.m. EDT yesterday on Oct. 9, NASA flight controllers in mission control, using cameras on the International Space Station exterior, observed flakes emanating from one of two radiators on the Roscosmos Nauka Multipurpose Laboratory Module (MLM). From here, the flight control team informed the crew aboard the space station of the potential leak, and NASA astronaut Jasmin Moghbeli confirmed the presence of the flakes from the cupola windows. She was quoted saying, “Yeah, there’s a leak coming from the radiator on MLM.” Soon after the crew was asked to close the shutters on U.S. segment windows as a precaution against contamination.

In addition to NASA’s observation, Roscosmos confirmed that the observed leak is on the segment’s backup radiator, which is mounted to the outside of the module. It was transferred to the Nauka during a Roscosmos spacewalk in April. The primary radiator on Nauka is working normally, providing full cooling to the module with no impacts to the crew or to space station operations.

However, since this radiator is mounted on the outside of the module, if they decide they need to intervene, it will require a spacewalk to reach the hardware. In only a few days from now on the 12th, NASA has a spacewalk planned which could be delayed because of the leak. It’s important to point out that Ammonia is so toxic that spacewalks near the substance must have extra precautions built in to reduce exposure risk to astronauts.

In terms of the hardware itself, the radiator was delivered to the space station during space shuttle mission STS-132 over a decade ago in 2010. Interestingly, the leaky backup radiator was originally for a different Russian module aboard the space station, called Rassvet. That was until a Roscosmos spacewalk earlier this year in April transferred the then-functional backup radiator to Nauka. Whether or not the problem that caused the leak happened between then and now is not clear.

In a statement from Roscosmos translated to English, they commented, “The main thermal control circuit of the module operates normally and provides comfortable conditions in the living area of the module. The crew and the station are not in danger. The work of the main operational management group continues to analyze the current situation” they said.

Looking at various NASA documents that go in-depth into ISS systems, highlight some of the dangers of leaking substances. For example, it’s quoted saying, “Because of the highly toxic nature of ammonia, IFHX ORUs are mounted external to the pressurized modules as a safety precaution. They go on to explain that “Waste heat is removed in two ways, through cold plates and heat exchangers, both of which are cooled by a circulating ammonia loops on the outside of the station. The heated ammonia circulates through large radiators located on the exterior of the Space Station, releasing the heat by radiation to space that cools the ammonia as it flows through the radiators. A similar system is currently leaking on Russia’s module. In the next few days, we can expect to hear more from NASA as they continue to investigate the problem and find a solution.

The Third Leak

Unfortunately, this leak joins a list of others all within the last year. Starting last year in December, during preparations for a planned spacewalk by Roscosmos cosmonauts, ground teams noticed significant leaking of an unknown substance from the aft portion of the Soyuz MS-22 spacecraft docked to the Rassvet module on the ISS. The spacewalk was canceled, and ground teams in Moscow began evaluating the nature of the fluid and potential impacts to the integrity of the Soyuz spacecraft.

Originally, the Soyuz carried one NASA astronaut and two cosmonauts on a launch in September. A couple days after the leak begun, Roscosmos identified the source of the leak as the external cooling loop of the Soyuz. As part of the ongoing evaluation and investigation, Roscosmos flight controllers conducted a few different tests of the spacecraft. The systems that were tested were nominal, and Roscosmos assessments of additional Soyuz systems continued.

Roscosmos maintained the cause was likely “a micrometeoroid or space debris.” The hole is roughly 0.8 mm in size and an object that caused a hole of that size would not be trackable with current technology, NASA and other space agencies have said. In total, the leak lasted around 3 hours long. As a part of the analysis, NASA even reached out to SpaceX about its capability to return additional crew members aboard Dragon if needed in an emergency, although the primary focus was on understanding the post-leak capabilities of the Soyuz MS-22 spacecraft. However, it was eventually decided that Russia’s space agency will launch an empty Soyuz capsule to the International Space Station in February to replace the damaged spacecraft that is unsafe to return its crew of three to Earth.

Only a few months later in February, NASA reported that engineers at the Russian Mission Control Center outside Moscow recorded a depressurization in the unpiloted Roscosmos Progress 82 cargo ship’s coolant loop, which is docked to the space-facing Poisk module at the station. At the time, the hatches between the Progress 82 and the station were open, and temperatures and pressures aboard the station were all normal.

The agency commented that NASA specialists were assisting their Russian counterparts in the troubleshooting of the Progress 82 coolant leak. Eventually, they decided to undock the spacecraft and deorbit it. Following undocking, Expedition 68 cosmonauts sent commands from the station’s Roscosmos segment to rotate the Progress for additional visual inspections of the general area where a coolant loop leak occurred on Feb. 11. Loaded with trash, Progress was deorbited by Roscosmos flight controllers over the Pacific Ocean after spending four months at the station.

Looking back even further, there have been a few other incidents with Russian ISS equipment. Faulty software aboard Nauka when it first docked with the ISS in July 2021, for example, briefly tilted the space station and caused NASA’s Mission Control to declare an emergency. A different Russian spacecraft in 2018 somehow ended up with a hole, which was plugged by orbiting astronauts before the spacecraft safely returned home.

Current plans call the for station to operate for the next 7 years or so before being retired and deorbited. With the exception of Roscosmos, the other partners have agreed to remain on station with NASA until 2030. Russia however, will withdraw no earlier than 2028 to pursue its own space exploration plans. This would mean they would be apart of the station for another 5 years or so.

When asked why the agency is retiring the ISS, NASA responded, “The International Space Station Program has maintained a continuous human presence aboard the microgravity laboratory for more than 22 years with assembly missions starting in 1998. Throughout the years, NASA and its international partners have worked together to operate, maintain, and upgrade parts of station. The technical lifetime of the station is limited by the primary structure, which includes the modules, radiators, and truss structures. The lifetime of the primary structure is affected by dynamic loading (such as spacecraft dockings and undockings) and orbital thermal cycling.

This old age and continued cost has pushed NASA toward the station’s retirement and destruction. Just recently the agency turned to the commercial industry for possible vehicles and spacecraft capable of de-orbiting the station. NASA was quoted saying, “The primary objective during space station deorbit operations is the responsible re-entry of the space station’s structure into an unpopulated area in the ocean. The chosen approach for safe decommissioning is a combination of natural orbital decay, intentionally lowering the altitude of the station likely using current propulsive elements, and then execution of a re-entry maneuver for final targeting and to control the debris footprint. This final maneuver is expected to require a new or modified spacecraft using a large amount of propellant” they said. All in hopes of transitioning to commercial options in the next decade.

Conclusion

Another leak was just reported at the ISS, this time with a Russian module. Right now both NASA and Roscosmos are investigating the issue and trying to determine the best course of action. We will have to wait and see how it progresses and the impact it has on the space industry.