A Closer Look At Blue Origin’s BE-4 Engine Explosion

For around a decade now Blue Origin has been developing and manufacturing the BE-4 engine. In that time the company has run into quite a few delays but still managed to produce a next-generation engine. Most recently we saw increases in production as the demand for these engines is expected to grow significantly in the coming months.

Unfortunately, yesterday reports came out that a BE-4 flight engine exploded 10 seconds into its static fire. This happened last month during acceptance testing at one of Blue Origins’ test stands. The explosion destroyed the engine and was responsible for a decent amount of damage to the test stand infrastructure.

Even more concerning is the problem itself and whether or not this issue could affect Vulcan, which currently has two BE-4 flight engines installed and ready for the maiden flight. Not to mention the production underway and plans with New Glenn. Here I will go more in-depth into the BE-4 explosion, what it means for Vulcan and New Glenn, what to expect in the coming weeks, and more.

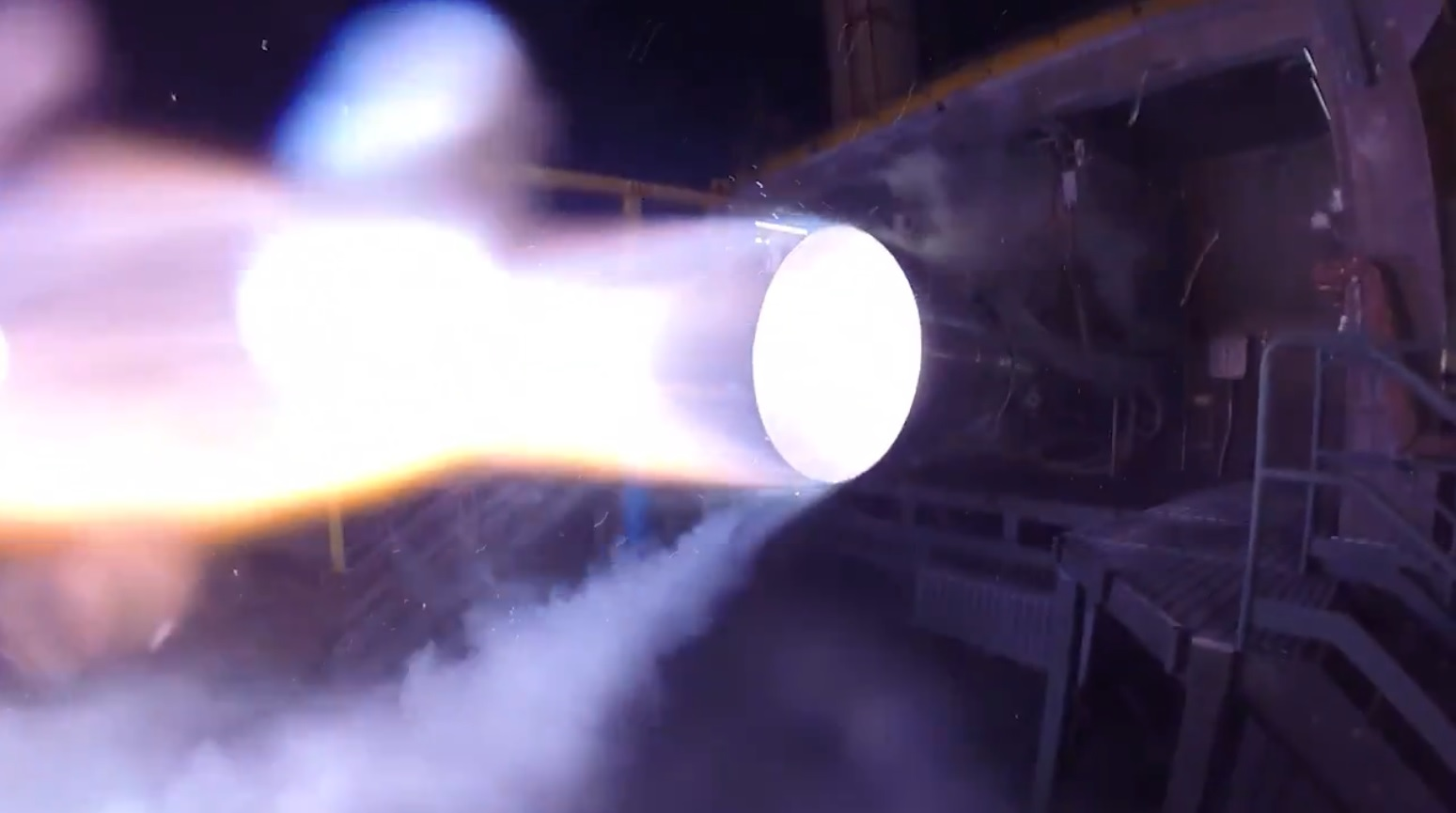

BE-4 Explosion

Yesterday, a Blue Origin spokesperson, in a statement confirmed the company “ran into an issue while testing Vulcan’s Flight Engine 3.” “No personnel were injured and we are currently assessing root cause,” Blue Origin said, adding “We already have proximate cause and are working on remedial actions.”

Despite the explosion Blue Origin pointed out that they will continue to test engines in West Texas and are confident they will be able to meet their engine delivery commitments this year and stay ahead of their customer’s launch needs.

With all this in mind, the main issue becomes figuring out why this engine exploded and whether or not it could be an issue on other engines in production or even installed on Vulcan. As partially mentioned prior, Flights engines 1 and 2 are installed on the bottom of the Vulcan booster. These engines have passed all the qualification testing by both Blue Origin and ULA as well. Later this year these engines are expected to ignite and launch Vulcan for the first time. This recent explosion however makes this process more complicated.

The best-case scenario and what both ULA and Blue Origin are hinting at is that the error was caused by poor workmanship. This would suggest that this single engine is the problem and that’s it. The worst-case scenario would be that a deep problem with the engine is present on all BE-4 hardware that was just revealed during this failed test.

Recently, Tory Bruno, ULA CEO, gave some insight into this failed test and its impact on Vulcan. First, when asked whether or not this failure would set back Vulcan’s maiden flight he responded, “Very unlikely. We always check every ATP anomaly for any cross over, but not expected here”. He continued by clarifying, “Sure. Every engine, elex box, COPV, etc, gets an Acceptance Test (ATP) as they come off the line to verify good workmanship. (The one time Qual verifies the design. BE4 is qualified). The BE4’s on Cert1 have passed ATP, as have many others. This engine failed ATP.” This suggests that the issue was indeed caused by bad workmanship and shouldn’t affect the engines that already passed on these tests installed on Vulcan.

He pointed out that anomalies like these are “Relatively routine at the beginning of a production run. Later, however, as the automated shutdown systems get well-tuned in, they become rare. He finished with one last comment that the issue is, “Way less interesting than it sounds. Just an ATP failure. They happen. That’s why we acceptance test each component coming off the line before accepting delivery.”

While these comments from Bruno are a good sign, a flight engine completing some of its final testing still exploded. No matter the case this will take time to investigate and cross-check other engines and components to ensure the explosion was a unique instance. Not to mention delays related to infrastructure destruction and debris.

As far as New Glenn, this explosion should have little to no impact on the larger rocket. New Glenn uses 7 of these engines on the first stage and is scheduled to lift off next year. As we haven’t seen any testing or for the most part updates on this rocket, there is likely a decent amount of time left before this rocket needs operational BE-4 engines. In that time Blue Origin expects to get this problem sorted and move on.

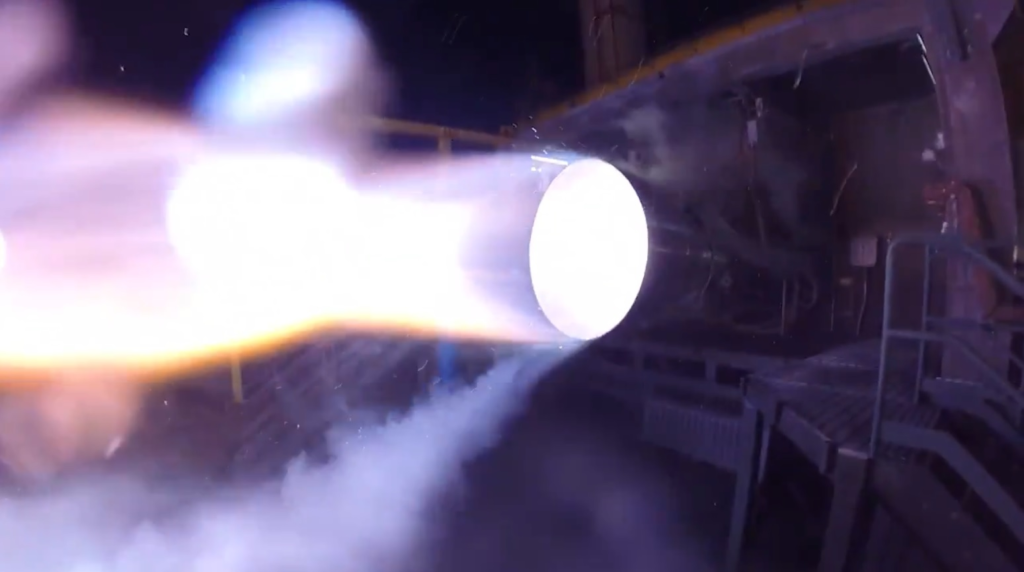

A Lot of BE-4 Engines

In recent months, Blue Origin had been ramping up this next-generation engine’s production by quite a bit. In October of last year, we first got a hint at this when the company said in a report that “Dozens of these engines are now in production to support a large and growing demand for civil, commercial, and defense launches.” More recently in April, they released footage inside the regen nozzle room in the Huntsville engines factory. Here dozens of BE-4 engines can be seen in early production. All of this in preparation for an increase in expected demand.

This demand comes as New Glenn and especially Vulcan prepare for a busy future. To put in perspective the amount of Vulcan launches expected, ULA CEO Tory Bruno commented, “We have to ramp up, before the end of 2025 we expect to be really at a tempo, which is flying a couple of times a month, every two weeks.” This amount of engines is a very big deal as it comes out to around 48 BE-4 engines a year. It’s also important to point out that United Launch Alliance has priority when it comes to receiving these engines. This means that Blue Origin will need to make enough engines for Vulcan and ULA first and then additional ones for each New Glenn booster.

A lot of this demand has to do with the fact that Vulcan is not reusable and each launch will use up two BE-4 engines. Even though the company does have some plans for Vulcan partial reusability, it might be a while. In another quote, Tory Bruno said, “In terms of our engine recovery, that is going to happen within a handful of years. I don’t want to say exactly when because it’s part of the contract we have with one of our customers at this time, and we’re not releasing the details of that. But it will take a couple of years to actually be reusing the engine.” He finished by saying, “You will see us potentially do more demonstrations. We’ll be collecting environmental data to see booster experiences. We’ll recover engines and look at them. And then eventually we’ll have the confidence to recover them, inspect them, and then reuse them. And so that will happen in this window of a few years, but it’s too early at this moment for me to say exactly when. But you’ll see that activity ramp up.”

In other words, the reusability of Vulcan and the two BE-4 engines is not a priority right now for ULA. This means that as Vulcan launch cadence increases, the demand for BE-4 engines will grow as well. As for New Glenn, the company will need to complete a host of tests with different components such as the engines. However, around this exact time period is when Vulcan launches are supposed to be at an all-time high. It’s also important to point out that rather than just two engines on the first stage, New Glenn requires 7. With such high demand Blue Origin needs to figure out exactly what went wrong on the recent test and ensure it doesn’t happen again. With so many engines being worked on right now for next-gen launch vehicles, they have practically no room for error and can’t afford to have a handful of defunct engines.

At the end of the day, BE-4 is a very complex system with unique design choices. The BE-4 was designed from the start to be a medium-performing version of a high-performance architecture. It’s a design choice the company made to try and lower development risk while meeting performance, schedule, and reusability requirements. For the propellant, they chose LNG because it is highly efficient, low-cost, and widely available. Unlike kerosene, LNG can be used to self-pressurize its tank. Also known as autogenous repressurization, this eliminates the need for complex and costly systems that draw on Earth’s helium reserves. LNG also possesses clean combustion characteristics even at low throttle, simplifying engine reuse compared to kerosene fuels.

In the coming weeks, Blue Origin will continue to investigate the engine anomaly until they are 100% sure they found the culprit. If necessary they will check other engines including ULA’s to make sure they don’t have a similar issue. Soon we can expect more information from Blue Origin and eventually a report on what happened. Tory Bruno continued to stress the idea that qualification tests determine if the engine design is good and works as intended. Acceptance tests or ATP check the workmanship and if the engine is manufactured as intended. They are confident that BE-4 is a great architecture and that this has been demonstrated through all of its rigorous testing. Hopefully, that’s the case and this issue was simply human error, unlikely to happen again.

Conclusion

The third flight engine that was going to ship to ULA in the coming months exploded late last month on the test stand. While by no means ideal and will cause a few delays for engine production, the hope and expectation is that it was a single-case anomaly. Other engines have passed all the various tests to ensure they are complete and ready for flight. We will have to wait and see how it progresses and the impact it has on the space industry.